African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 12: Picking a candidate proves tricky for a divided party

The 1888 Republican convention was uncharted territory for many delegates, with no clear frontrunner and a wide-open field. James G. Blaine, the party’s 1884 nominee and a narrow loser to incumbent president Grover Cleveland, had opted out of contention, although his supporters continued to see themselves as kingmakers in a contested race.

Of more than a half dozen men eventually nominated, Ohio’s Senator John Sherman, a former Treasury Secretary, was perhaps closest to becoming a consensus nominee on his third successive try. After the early death of Democratic Vice President Thomas Hendricks in 1885, Sherman had been next in line for the presidency, after being elected president pro tempore of the Senate, until he resigned from the pro tem office to campaign for the presidential nomination.

He was favored by many Southern delegates, who cast 122 votes for him on the first ballot, half his national total. It is difficult to gauge specific support for Sherman among the black delegates, but it appears that at least half of the 61 black delegates favored Sherman. Because votes by specific delegates were not uniformly listed in convention proceedings, only a handful of states whose results were challenged listed individual votes by each delegate: South Carolina, where seven black delegates chose Sherman; Louisiana, where four black delegates favored him; Virginia (2); and Tennessee (1).

Challenges on subsequent ballots revealed two black votes in Texas (second ballot) and four black votes in North Carolina (third ballot). And it is certain that as least six Georgia delegates—and perhaps as many as all nine—voted for him on at least the first ballot, when 19 of the state’s 22 votes went to Sherman. So it appears that at least 26 black delegates cast at least their first ballot for Sherman.

Other candidates with lesser support from black delegates included Judge Walter Gresham, the candidate most favored by Mississippi’s John Roy Lynch (11 votes from the South); and former Michigan governor Russell Alger (40 votes from the South), who drew at least four (named black) votes, and perhaps as many as 11. Despite his strong record as a Union general during the Civil War and his support for civil rights, eventual nominee Benjamin Harrison, a former U.S. Senator from Indiana, failed to inspire much Southern enthusiasm or black support on the first seven ballots.

Speakers who seconded the nominations of both Sherman and Gresham showed the friendly rivalry between black delegates supporting the two men. Virginia delegate John Mercer Langston, a Sherman supporter, gave an impassioned endorsement of the Senator and former Treasury Secretary: “Seven millions of Negroes to-day in this country ask you to nominate John Sherman to the Presidency …

Gentlemen have told you how great he is and grand, what a patriot he is and what a statesman, how loaded he is along all his arms, across his shoulders, all over his back, with the broken shackles fallen from the limbs of American slaves, the eternal marks of honor of his manly deeds.

Do you want to make your candidate National? … and would you add to the certainty of your victory by the carrying of all Virginia and North Carolina? Alabama? Tennessee? … If so, give us that paragon of American statesmen, and we will unite … Virginia, and carry that old Commonwealth …

Let me tell you, gentlemen of the convention, that the name of John Sherman is a wonderful thing in the South to-day. It is a tower of strength to the Negro, the poor white man and the Republicans in the South, too. And now, in the name of all the citizens of my state …in the name of the loyal South, white and black, aspiring, longing to be protected, defended, that they may exercise a free ballot and have it counted, I arise to second the nomination of this citizen of Ohio, now so grand a citizen of our entire republic, John Sherman.

In his autobiography, penned some 50 years later, Lynch recounted his own journey to make it onto Mississippi’s delegation, as a longtime supporter of Gresham, whom he considered “the strongest and most available man for the nomination.” He was well aware that “a decided majority of the Republicans of my state were favorable to candidacy of John Sherman. But this did not prevent my selection as one of the four delegates at large,” as long as he pledged to support Sherman as his second choice. The loser in Mississippi’s selection process, as noted in my previous blog entry, was former U.S. Senator Blanche Bruce, who had up until now been close ally of state party leader James C. Hill.

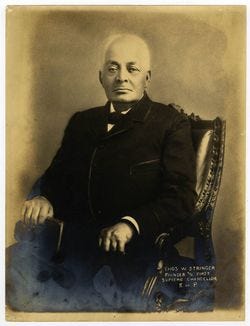

Both men favored Sherman, and Hill actually managed the wealthy Bruce’s business interests in his frequent absences. Bruce was on a lecture tour across the nation when Hill drew up the list—and decided, for reasons known only to him, to push Bruce off the delegation without informing Bruce—in favor of Dr. Thomas W. Stringer of Vicksburg. Stringer, a well-regarded party member with decades of convention experience, was the head of the colored masonic order …[and] could be of more service to him in the future.” Bruce was “apprehensive that his failure to be chosen … would be accepted by the [Harrison] administration … as evidence of the fact” of his declining importance in Mississippi.

Dr. Thomas W. Stringer, Mississippi delegate in 1888. Photo courtesy Xavier University of Louisiana Library Digital Archives & Collections

In Chicago, Lynch himself encountered Bruce, who was “very much incensed” at the news of Hill’s perfidious behavior. Their friendship was now destroyed. So much for intraparty harmony. Bruce broke all relations with Hill. Lynch and Hill had crossed horns once before, in 1880, but still remained on more or less cordial terms; Lynch does not mention his own relationship with Dr. Stringer, who was probably unaware of the situation or his unintentional involvement.

Lynch considered Sherman a strong second choice if Gresham could not be nominated. But his full-throated endorsement of Gresham left no doubt in anyone’s mind as to who he preferred:

He is in great measure at least the favorite son of the United States. His friends, his admirers, his supporters may be found all over the country—from Maine to California, from the gulf to the lakes. At any rate, I am satisfied that should he nominated our party will be saved. …

He was one of the organizers of the Republican party; one of the men who brought it into existence … A brave, gallant soldier who worked his way up from poverty: the friend of the laboring man, the friend of all honest men, and I believe and hope he will be the choice of this convention.

Lynch conceded that “we of the South” could contribute little to the Republican nominee’s victory in November, “in consequence of circumstances which we are unable to control.” But “if you gentlemen from the Northern States, from the doubtful States, were united among yourselves, we of the South would fall in line and help you to nominate your choice; but you are divided, and consequently we are divided.” Therefore there would be no “solid South” at the convention, at least.

Sherman would hold steady at nearly 250 delegates of the 416 needed, until the fifth and succeeding ballots, as Benjamin Harrison slowly gained strength. By the seventh ballot, what had seemed a near-solid South for Sherman—despite Lynch’s prediction—would have all but collapsed. Harrison would sweep the top spot on the eighth ballot, with New York’s Levi P. Morton then chosen as his running mate. This time, Bruce’s 11 votes would not be close.

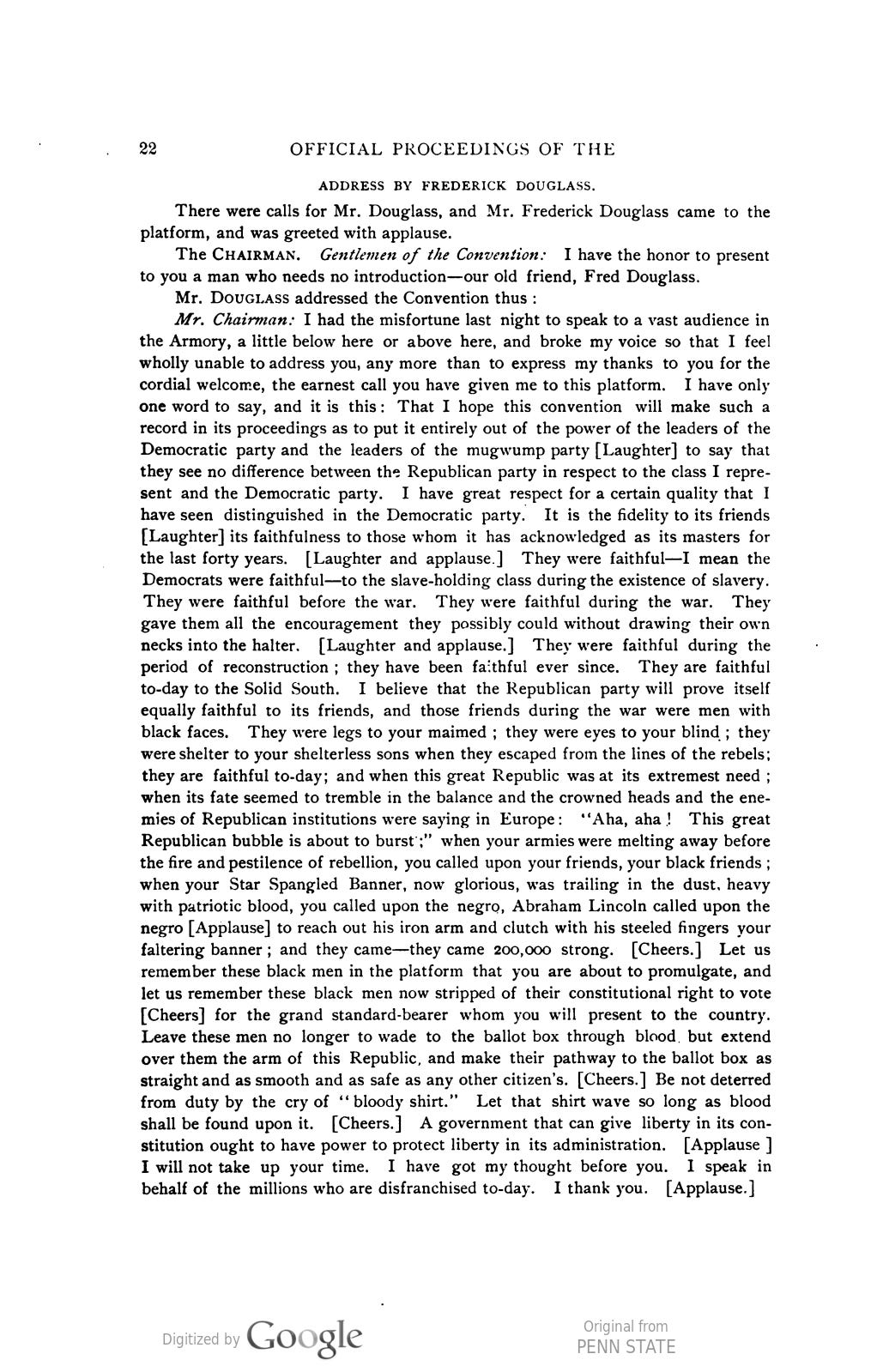

For all their eloquence, however, neither Lynch nor Langston could top the appeal of the convention’s single most notable black speaker—the venerable Frederick Douglass, whose hoarse whisper captivated his listeners in his brief speech, from his opening satirical ridicule of “faithful” Democrats (“faithful—to the slaveholding class during the existence of slavery”) to his closing admonition, offered on “behalf of the millions who are disfranchised today”—“A government that can give liberty in its constitution ought to have power to protect liberty in its administration.”

Frederick Douglass, longtime abolitionist and speaker at 1888 convention. Photo courtesy National Park Service

* * * * * * *

Both veteran and lesser-known black delegates would gain other measures of distinction at the 1888 convention. Seven delegates, for instance, were named to the Organizations Committee—including Virginia’s Langston and North Carolina’s John H. Williamson, a well-regarded journalist and longtime state legislator; Henry C. Ferguson of Texas, Samuel Petty of Florida, Isaac N. Carter of Mississippi, D. W. Ellison of Arkansas, and Wesley Crayton of Mississippi.

John H. Williamson, NC delegate in 1888. Engraving from The Afro-American Press and Its Editors (1891).

Wesley Crayton, Vicksburg businessman and Mississippi delegate in 1888. Public domain photo

Four black delegates would serve on the influential Credentials Committee, including James J. Spelman of Mississippi, Alabama’s John W. Jones, South Carolina’s J. M. Freeman, and Tennessee’s former legislator Samuel McElwee. John Lynch and South Carolina’s George E. Herriott would serve on the Resolutions Committee, while four other delegates were named to the Rules Committee: former Virginia legislator Alfred W. Harris, Georgia’s Jackson McHenry, Louisiana’s Napoleon LaStrapes, and Mississippi’s George F. Bowles.

Journalist James J. Spelman of Mississippi, delegate in 1888. Engraving from The Afro-American Press and Its Editors (1891).

Alfred W. Harris, Virginia delegate in 1888. Photo courtesy Special Collections, University of Virginia

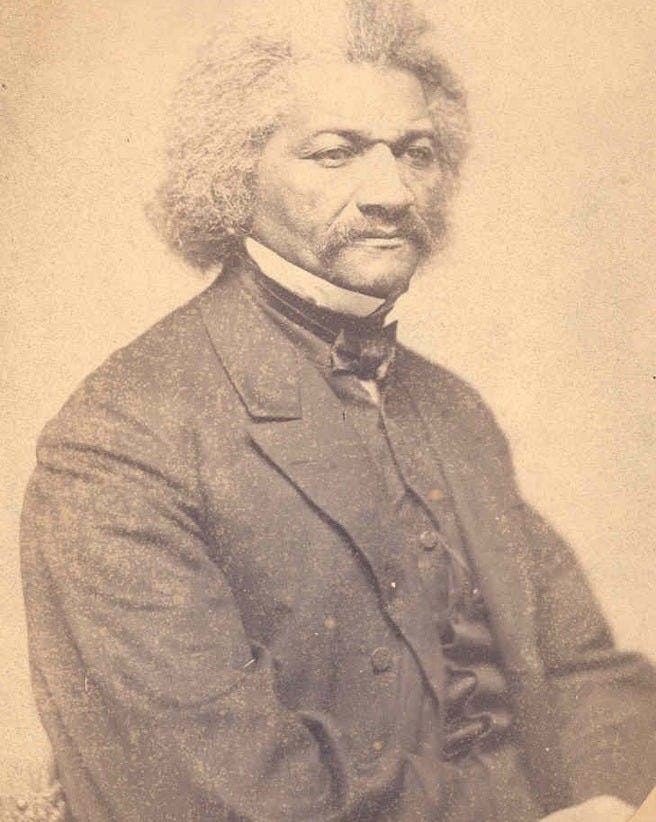

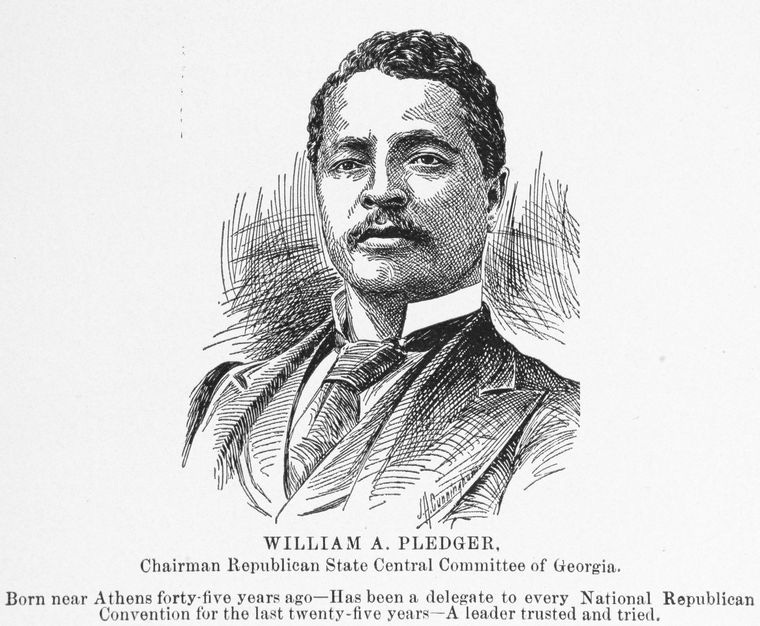

Although their ranks had recently begun to dwindle, veteran black politicians would continue to return to the party’s conventions in 1892 and beyond. Such familiar delegates as longtime Columbia, South Carolina, postmaster Charles M. Wilder and former congressman Robert Smalls, and Pinckney Pinchback of Louisiana, all of whom had first attended in 1868, would see calls to future duty. Perennial delegates John Lynch, John Williamson, William A. Pledger of Georgia, and Edmund Deas were among other returnees in the decades ahead.

Journalist William A. Pledger, Georgia delegate in 1888. Engraving courtesy New York Public Library

In all, at least 16 veterans of 1888 would be in Minneapolis. Three well-known faces, however, would not return for conventions, in 1892 or indeed, ever again. For Blanche Bruce, the 1888 convention would be his last appearance on the party’s national stage, although he would soon gain appointment in the new Harrison administration as Recorder of Deeds in the District of Columbia, one of the so-called “top four” black positions in the federal government. That he was also nominated as vice president, garnering 11 votes, was a fitting tribute to the nation’s only black full-term U.S. Senator.

For Thomas Stringer (1815-1893), who had first attended in 1868, and then replaced Bruce on the delegation in 1888, Chicago would mark his final appearance as a Mississippi delegate. At least one other familiar face would not return to the 1892 Republican convention, scheduled for Minneapolis: five-time veteran delegate, James H. Harris of North Carolina, a former congressional candidate, journalist, Union Army recruiter of black solders in the Midwest, and longtime state legislator who had gained a national following of no small repute. He had attended every national convention since 1868, when he was first named an alternate delegate, and previously served as a delegate to the gatherings in 1872, 1876, 1880, and 1884.

Although still comparatively young, at 56, his days were already numbered. He would move from North Carolina to pursue a new career in Washington, D.C., in late 1890, and would die there of natural cases in the spring of 1891. As recounted on the front page of the city’s largest newspaper, the Raleigh News & Observer, in early June (“Death of James H. Harris”)—a rare honor for an African American politician in that era—his remains were brought back to Raleigh for burial at the city’s Mount Hope Cemetery, where his widow and two of his children are also buried.

The Minneapolis convention in 1892 would be the farthest northern location so far for the party’s quadrennial celebration, after nearly a decade in Chicago.

Next time: Minneapolis offers a new perspective for black Republicans in 1892