African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 19: Gathering in Chicago to renominate Theodore Roosevelt in 1904

I conclude the chronicle of excerpts from my ongoing historical research into African American participation in Republican national nominating conventions—the subject of a planned book—with this week’s opening look at the setting in 1904, nearly four decades after the first 12 black delegates attended their first GOP convention in 1868.

Over the past 36 years, black delegates had become fixtures in delegations from most Southern states, although exact numbers are not available. The Official Proceedings of those conventions provide the names and residences of almost all delegates to each convention, but do not identify the race of any delegate. My own exhaustive analysis of delegate lists and cross-checking comparisons to other historical documents and newspaper accounts identified almost all black delegates to each convention, showing an average attendance of 63 black delegates identified since 1872, with an average of 56 black alternate delegates.

Attendance by black delegates had peaked in 1896, at 75, representing 11 states—Nebraska and 10 Southern states (all except Tennessee, which sent only black alternates that year)—and the District of Columbia. In that same year, some 70 black alternate delegates had been selected by 23 states and the District. But with disfranchisement looming across much of the South, the number of black delegates took a significant downturn four years later; in 1900, just 53 voting black delegates were identified. (The number of black alternates, conversely, was the second highest total since 1872, at 70.)

By 1904, America’s black Republicans had become far more familiar with Theodore Roosevelt than they had been at the 1900 GOP nominating convention. He had, of course, succeeded William McKinley six months after they were inaugurated in March 1901—and had presided with much success over a somewhat tumultuous political transition. If delegates in 1900 had mixed feelings about him as McKinley’s running mate, their options that year had been limited; W. Calvin Chase actively touted New York lieutenant governor Tim Woodruff, for instance, but his proposal gained no traction.

In 1904, their practical options were all but nonexistent, and any lingering opposition among black delegates to Roosevelt—and his chosen running mate of Senator Charles W. Fairbanks—was far more muted. Most of the 62 black delegates in 1904 were far more concerned with the growth of the “lily-white” Republican party across the South, and the rancorous competition between lily-whites and the “black and tan” wings of the party in Louisiana and South Carolina, for instance.

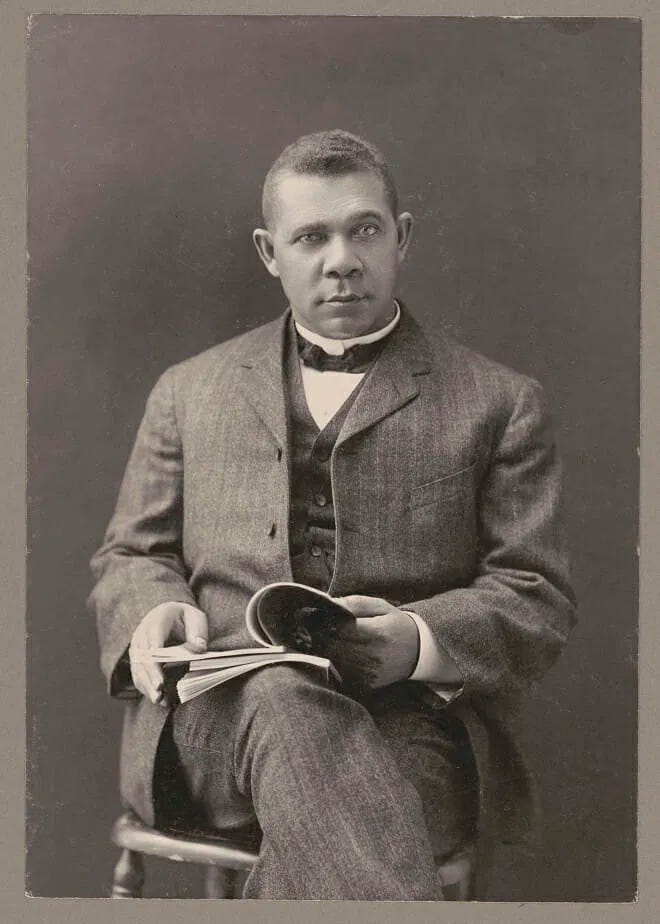

From all appearances, Roosevelt did not care much for the prospects of black Southerners. He had seemingly done little, if anything, to discourage the growth of lily-white politics in the South—while simultaneously engaging the services of Alabama educator Booker T. Washington as his effective gatekeeper in vetting black aspirants for patronage appointments.

Booker T. Washington, Theodore Roosevelt’s gatekeeper for black appointees. Photo courtesy Encyclopedia of Alabama

Washington was viewed by many black leaders with guarded suspicion; radical critics such as W.E.B. Du Bois displayed growing distaste and openly opposed his accommodationist stance. After the public-relations disaster surrounding his family dinner at the White House shortly after Roosevelt’s succession in the fall of 1901, he had cautiously approved only a handful of nominees for significant federal jobs since October 1901. The disgraceful performance of one of those—Dr. John R. A. Crossland of Missouri, the U.S. Minister to Liberia, who was recalled after a personal scandal just eight months into his 1902 appointment—made Washington even more cautious.

Onetime US Minister to Liberia, Dr. John R. A. Crossland. Photo courtesy www.findagrave.com

Unlike his predecessor, Roosevelt was far less inclined to appoint blacks to mid-level or lower federal positions, including U.S. postmasters, although he agreed to appoint Tuskegee’s first black postmaster, Joseph O. Thompson, in January 1902, probably at Washington’s suggestion. Thompson, a wealthy businessman, resigned less than a year later.

Joseph O. Thompson and his family at their Tuskegee home. Photo courtesy Alabama State Archives

Only two other black postmasters appointed during his first term were new to the job; the rest of the black postmasters approved during the first Roosevelt term were actually extensions given to McKinley postmasters previously appointed in 1898 and 1899.

During his first term, William McKinley had appointed at least 100 black postmasters, most of them in the South. By contrast, Roosevelt approved fewer than three dozen, although he did allow most McKinley appointees to remain on the job for second terms, including Minnie G. Cox of Indianola, Mississippi. Mrs. Cox had first served from 1891 to 1893 under former President Harrison; she was reappointed by McKinley to a four-year term in May 1897, and then given a second four-year term in the spring of 1901, months before McKinley’s death.

The popular schoolteacher served without incident until 1903, when her race suddenly became a flashpoint. Local segregationists suddenly demanded her early termination, in favor of a less-qualified white man. But to his credit, Roosevelt said no, refusing to accept her resignation, and instead chose to shut down the post office completely—while keeping her on the payroll—after she fled the town in the face of death threats.

Minnie Geddings Cox, postmaster at Indianola, Mississippi, 1897-1904. Public domain photo

After fleeing to Alabama, she eventually resigned rather than return to Indianola, but Roosevelt remained angry, reopening the post office grudgingly only a year later because federal law required post offices to operate in county seats.

From the outset, Roosevelt was less than enthusiastic about other black appointments, and in his first term, appointed or reappointed fewer than a dozen mid-level black officials for posts such as customs collector or receiver of federal monies. It stemmed in part from his early disenchantment with one high-ranking holdover from the McKinley era: Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia Henry P. Cheatham, a former congressman first tapped by McKinley in May 1897.

The Recorder’s post was one of the “top four” black appointments that past presidents had bestowed on well-regarded applicants; the others were the U.S. Treasury Register (Judson W. Lyons, appointed in 1898), and ministerial posts to Haiti (William F. Powell, since 1897) and Liberia (Rev. Ernest A. Lyon, since 1903).

McKinley had initially been inclined to recommend Cheatham for a second four-year term, but died before sending the nomination to the Senate; weeks later, Roosevelt was then alarmed when a major scandal—never publicly explained—erupted in the fall of 1901, apparently linked to improprieties said to have been committed by either Cheatham or one of his staff members.

The brouhaha began when former McKinley adviser Benjamin W. Arnett protested the dismissal by Cheatham of his son Henry, a high-ranking clerk in the large office. A thorough investigation conducted by Attorney General Philander Knox cited an unspecified but “serious technical infraction of federal law,” and Cheatham was forced to resign quietly to put the matter at rest. (I discuss the scandal at length in the epilogue to my 2020 book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality.)

Henry P. Cheatham, Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, 1897 to 1901. Public domain engraving

According to newspaper reports at the time, there was a darker, more salacious subtext to the situation. Following his wife’s death in 1898, Cheatham had allegedly courted an unnamed woman to the point of engagement, but abruptly decided not to marry her. Roosevelt was said to be so disturbed by the breach-of-contract rumors that he refused to consider retaining Cheatham in his administration, despite his recent marriage. (Both scandals would certainly have provided ample fodder for the press during any Senate confirmation hearing.)

Thus Cheatham was succeeded in January 1902 by John C. Dancy, a religious journalist and distinguished federal appointee in Wilmington, North Carolina, who sailed through confirmation with no obstacles. Cheatham returned to live in North Carolina, where he became director of a large orphanage for black children in Oxford. There are some indications that he sought but never received another federal appointment.

In an ironic twist, perhaps, both Cheatham and Joseph Thompson were selected as delegates to the 1904 convention which planned to nominate their former boss for a full term.

* * * * * * * *

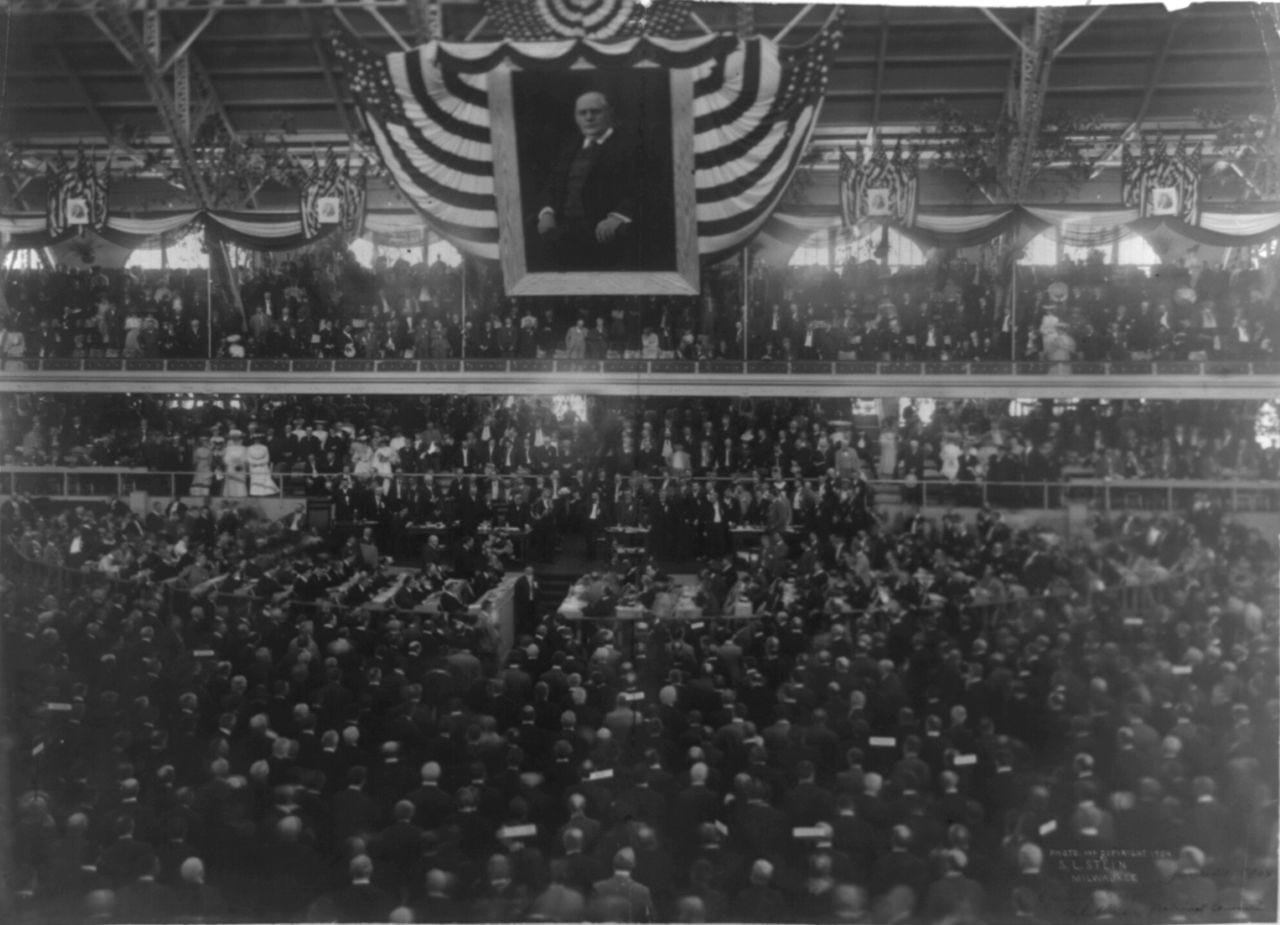

Built in 1899, the third Chicago Coliseum was located at Wabash Avenue near 15th Street, on the near south side. Beginning in 1904, it played host to five consecutive Republican national conventions.

The third Chicago Coliseum in 1904, host to five consecutive GOP conventions. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

The Coliseum was a colossal building, if perhaps a bit too large for the convention it first housed in 1904. It had actually featured indoor college football games and horse shows, and its 6,000-seat arena could be exapnded with floor seats to hold up to 16,000 people. It was so cavernous, in fact, that thousands of tourists and visitors were eventually given free tickets by the party to visit the convention sessions to avoid having it look too empty, according to the New York Times.

Opening prayer for the 1904 convention in the vast Coliseum building. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

And although the 1904 convention was carefully planned as a sort of coronation for President Roosevelt, the hall was dominated by the huge flag-draped portrait of his predecessor, the late President William McKinley, which hung over the stage.

Black delegates from 12 states and the District of Columbia gathered during the convention’s opening session on June 21, among them a city councilman from Baltimore, Maryland, Harry S. Cummings, who would offer a spirited endorsement of President Theodore Roosevelt.

Harry S. Cummings, Maryland delegate to the 1904 convention. Public domain photo

Next week, I will examine the events which took place at the 1904 convention.

Next time: Singing Roosevelt’s praises to fans and doubters alike in 1904