African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 14: Minnesota provides a welcoming change of pace for black Republicans

Among American cities, Minnesota’s largest was no metropolis—not yet, at least—but it was already a pleasant and growing city. Republicans had chosen it to host their 1892 national convention with an eye to broadening the party’s appeal in the Midwest and beyond, after nearly a decade of consecutive gatherings in Chicago.

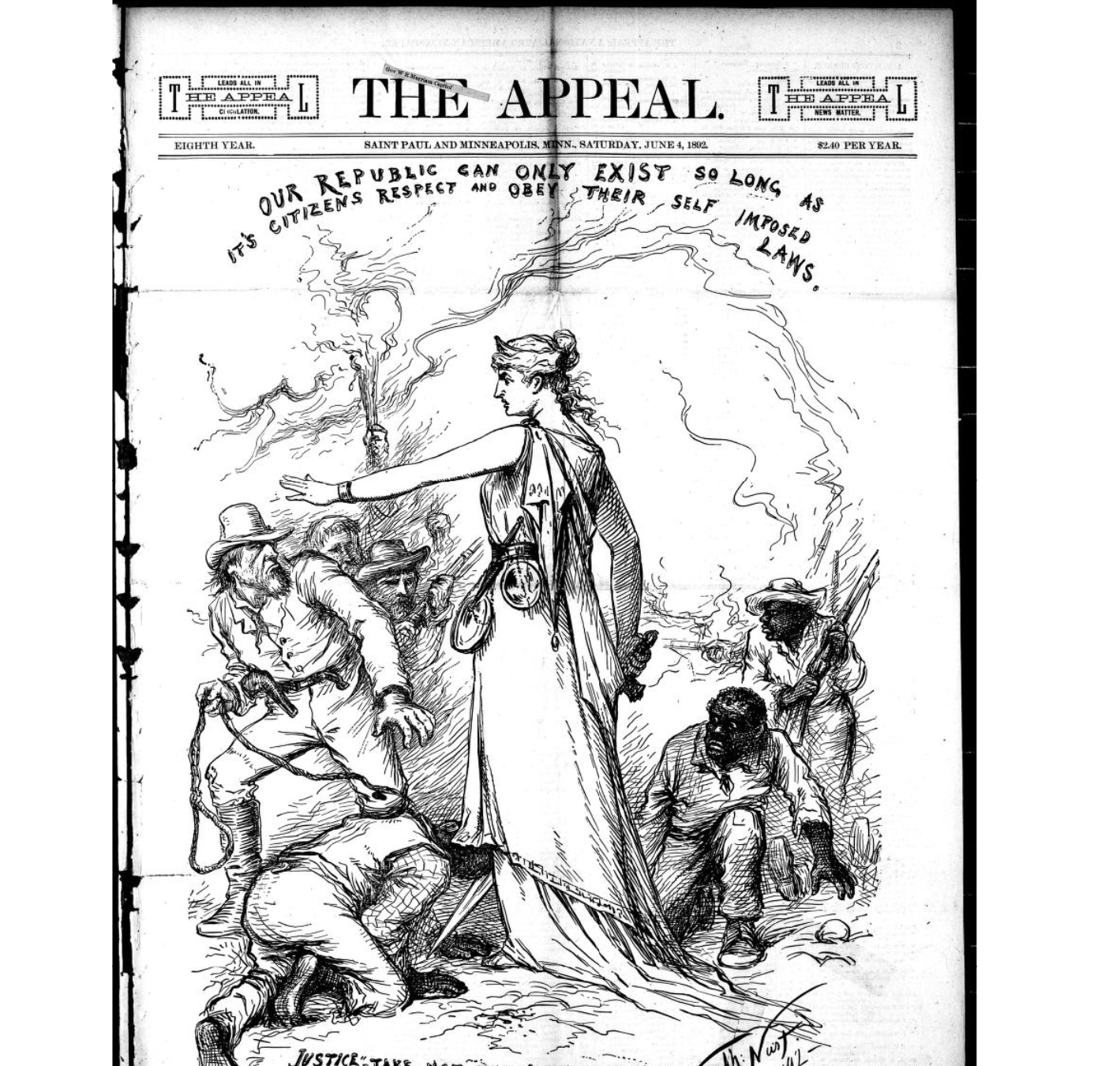

Minneapolis remained overwhelmingly white, with an African American population smaller than that of many major U.S. cities, at less than 1,000 in the 1890 census—about 0.5 percent—and about half the size of the black population in nearby Saint Paul, the state capital. The Twin Cities did boast a number of large African American churches, and even a well-regarded weekly newspaper, The Appeal, edited by a former Republican alternate delegate, John Quincy Adams of Kentucky.

Front page of The Appeal, dated June 14, 1892. Courtesy of www.chroniclingamerica.gov.loc

From his base across the Mississippi in Saint Paul, the staunch Republican published his newspaper with regional offices in Chicago, Dallas, Saint Louis, and Washington, D.C. Adams’s newspaper was funded in part by the Republican party, according to historical accounts, although his fervor for civil rights and equal justice well exceeded the average party line. A co-founder of the Protective and Industrial League of Minnesota, with a young activist lawyer named Fredrick L. McGhee, Adams had devoted a recent front page of his paper to a recent Thomas Nast cartoon that clearly expressed his passion.

“Justice, take not the law into your own hands, for where will that end.” Thomas Nast cartoon of 1892, public domain

Black Americans around the nation had held a national day of fasting and prayer days earlier on May 31, at the request of the St Louis Committee and supported by the National Afro-American League (an early civil rights organization, of which Adams and McGhee were members), to protest against widespread lynchings in the American South. Well-attended gatherings at black church in both Minneapolis and Saint Paul on May 31 received coverage in local media, including the Appeal, and reflected growing local interest in the unfair and violent treatment facing African Americans across the South.

The Appeal reported on June 4 that more than 500 “colored delegates and other visitors” were expected to be in the metropolitan area during the convention, including familiar political faces—former congressmen John M. Langston and John Roy Lynch, both delegates, and onetime delegates Blanche K. Bruce and P. B. S. Pinchback, as well as perennial attendee Frederick Douglass—and a handful of lesser-known luminaries, such as two college presidents: the Rev. Joseph C. Price of the venerable Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina, and Richard R. Wright, Sr., a Georgia delegate who headed the recently-founded Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth in Savannah. Price also served as president of the nationwide National Afro-American League, and Wright was expected to deliver a lecture of interest to the local population.

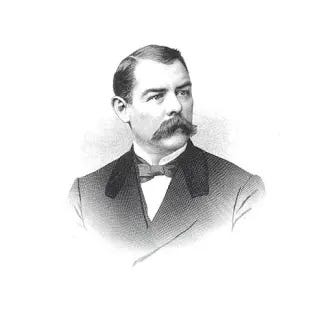

College president Joseph C. Price, among non-delegates expected in Minneapolis in 1892. Public domain photo

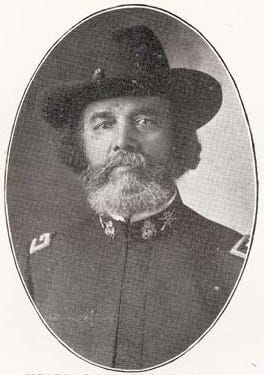

College president Richard R. Wright, Sr., 1892 delegate who lectured in Minneapolis. Public domain photo

Other speakers scheduled during early June included the Rev. Theophilus G. Steward, a longtime U.S. Army chaplain for the Army’s all-black Twenty-Fifth Regiment, and former North Carolina Judge Albion W. Tourgee, a white Reconstruction leader still famous for his best-selling 1879 novel, A Fool’s Errand, and an 1880 novel, Bricks Without Straw, both loosely based on his experiences in the postwar South.

Albion Tourgee, who lectured in Minneapolis in June 1892. Public domain photo

Chaplain Theophilus G. Steward, who spoke in Minneapolis in 1892. Public domain photo

Local committees made careful plans to entertain many of the visitors, including one “Grand Reception” planned by 50 of Saint Paul’s female residents—a free “elegant supper” and “rich and varied programme of music and speeches” at the city’s Market Hall—while for entertainment, two performances by the Capital City Band of Washington, D.C., one in each city.

If there were no black delegates or alternates from Minnesota on the convention floor—despite an intensive, unsuccessful effort to have McGhee selected as one alternate—local residents paid close attention to the performance by black visitors from other states, as did mainstream white media. “The [black] members of the Southern delegations find themselves of considerable importance today, and appear to appreciate the fact. The Harrison men are making strong efforts to hold them in line, while the anti-Harrison men are using all the means at their command to break into the South,” wrote the St. Paul Daily Globe as the convention neared a vote (“Buying Black Men,” June 7).

Fred Douglass, notwithstanding his age [74], is actively at work in the Harrison cause, addressing the colored men and stiffening the lines where they are inclined to waver. At the Georgia headquarters he addressed the whole delegation while it was engaged in perfecting its organization. The Georgia delegation, it has been asserted, were solid for Harrison, but a suspicion developed that some of them were unreliable, and Mr. Douglass urged them to stand firm and true. …

Ex-Senator Bruce, Auditor Lynch, and other colored men are working for Harrison. An effort was made to win over Mr. Langston to the president’s support, but he told the committee in an outspoken, vigorous manner that he was on the other side.

Rumors swirled that black delegates were being offered money to change their votes, although no proof was given, although Harrison campaign workers “claim to have information positively from some of the Negroes who were approached by Mr. Blaine’s friends.” Such allegations, the Daily Globe pointed out, tended to circulate at every Republican convention.

* * * * * * *

As the first ballot proved, Harrison retained his predicted strength within Southern delegations, with Alabama, Florida, and Georgia unanimous in their support, and only Langston’s Virginia actually favoring Blaine. The vice presidential nomination caused only a small bit of excitement, when a black delegate from Tennessee, Josiah T. Settle, insisted on nominating longtime Congressman Thomas B. Reed of Maine against the consensus choice, Whitelaw Reid—purely on principle.

Reed, a former House Speaker, was “a man who believes that citizenship in Tennessee or Louisiana is entitled to the same protection that it has in New York or Connecticut,” said Settle, a well-regarded Memphis attorney, former state legislator, and former prosecutor. “He is as intensely American as any man who breathes air upon the American continent—a man who has demonstrated to the American people his ability at all times and under all circumstances to make American citizenship respected all over this broad land,” particularly by facing down opposition in the House from Southern Democrats over the controversial Federal Elections Bill of 1890, which failed in the U.S. Senate.

If still important to the cause of black equality, Settle’s effort was purely symbolic: Thomas Reed’s name was duly withdrawn, when it was discovered he had not been properly consulted, and Whitelaw Reid, the influential journalist and former Minister to France, was swiftly nominated by acclamation, without an actual vote.

It was the first time since 1880 that former Senator Blanche Bruce—a backstage presence only in 1892—received no votes in the vice presidential ballot. Thomas Reed, whose name was withdrawn, would later be reelected as House Speaker in 1897, while nominee Whitelaw Reid would be defeated for vice president in the general election, when former President Grover Cleveland defeated incumbent President Harrison in their second matchup.

In recognition, perhaps, of his personal reputation, Settle himself would continue to attend Republican conventions for more than a decade, if only as an alternate delegate from Tennessee. In 1892, Settle would also gain appointment to a convention committee—the influential Credentials Committee, along with Thomas S. Cage of Louisiana and Andrew Gleason of the District of Columbia. The single largest number of delegates—six in all—would be named to the Rules Committee, including Joseph E. Lee of Florida, Edward S. Richardson (Georgia), Louis J. Souer (Louisiana), Edward A. Johnson (North Carolina), William D. Crum (South Carolina), and John Mercer Langston (Virginia).

Four black delegates and one alternate would serve on the Committee on Permanent Organizations, including Georgia’s John Quincy Gassett, J. Madison Vance of Louisiana, Wesley Crayton (Mississippi), Hugh Cale (North Carolina), and John W. Freeman (alternate, District of Columbia). Another four black delegates would be named to the Resolutions Committee: Richard Wright of Georgia, Robert F. Guichard (Louisiana), Samuel E. Smith (South Carolina), and Perry Carson (District of Columbia).

Honorary state vice presidents chosen by their delegations included black delegates Ferd Havis of Arkansas, Singleton H. Coleman (Florida), William A. Pledger (Georgia), Paris Simpkins (South Carolina), and alternate delegate John W. Freeman (District of Columbia). Five black honorary state secretaries were also selected: William R. Long of Florida, John C. Dancy (North Carolina), John H. Fordham (South Carolina), James C. Napier (Tennessee), and Andrew Gleason (District of Columbia).

Four black delegates would be named to the separate notification committees for President Harrison and Vice President-designate Whitelaw Reid. Those selected to visit President Harrison were James A. Spann of Florida, Congressman Henry P. Cheatham of North Carolina, Edmund H. Deas (South Carolina), and Perry Carson (District of Columbia). Chosen to visit Reid were Alabama’s Anderson McEwen, James H. Young of North Carolina, John H. Fordham (South Carolina), and Andrew Gleason (District of Columbia).

* * * * * * *

After completing its visit to the Northern Midwest, the convention would reconvene in 1896 in Saint Louis, Missouri, the southernmost city yet to host a Republican gathering. At least two dozen experienced black delegates would return, but for at least two veterans, 1892 would mark their last appearance upon the party’s national stage.

Former Congressman John Mercer Langston would continue to lecture and in 1894, would publish his autobiography, From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol. But he would decline to seek reelection to Congress in 1892, and perhaps for reasons of failing health, would not serve as a Republican convention delegate from Virginia in 1896.

Frederick Douglass, the valiant old warhorse of abolitionist politics and a longtime public servant, would also issue a revised version of his 1881 autobiography in 1892. Still active to the day of his death, when he delivered a stirring address to the National Council of Women, he died of natural causes at his home in Washington in February 1895, at age 77.

Next time: Gathering in Saint Louis, Republicans seek a comeback