African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 1: Before they were famous--or could even vote--black rising stars from South Carolina attended the 1864 Republican convention

Before they could even legally vote, a handful of black South Carolina politicians-in-waiting—including a future U.S. Congressman—attended the 1864 Republican national convention, which renominated Abraham Lincoln for the presidency.

But did they actually get to vote there? It appears not, if only because their state delegation was disqualified from voting at the Baltimore National Union Convention when they arrived—but their mere presence at the Front Street Theatre was both symbolic and emblematic of their future importance.

This week, I am shifting gears, temporarily, from my recent entries on foreign affairs—my occupation while a Foreign Service Officer for the Department of State for nearly 15 years—to return to my academic research in African American political affairs of the 19th century, with an upcoming book in mind.

At least three African American military personnel—two of them members of the oldest black Army regiment authorized by Lincoln, the First South Carolina Volunteers, in 1862—were among 16 members of a provisional delegation selected by Beaufort County organizers on May 17, 1864, to the Baltimore convention which would renominate Lincoln a month later.

The names of delegates Robert Smalls, Prince Rivers, and Henry Hayne—soon to become household words in post-Civil War South Carolina, at least—appeared in a lengthy article printed days later by the Beaufort Free South, a weekly newspaper published in the small Union-occupied city on Port Royal island. All three had achieved distinction in their brief military careers, Rivers and Hayne as sergeants in the all-black First South Carolina Volunteers, stationed at Port Royal, recently renamed the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) regiment.

Smalls—the cunning enslaved pilot who daringly commandeered a new steamship leased to the Confederate Navy and sailed it into Union hands in early 1862—was a Navy man, well known across the nation as the first black pilot, later a captain, in the Union Navy.

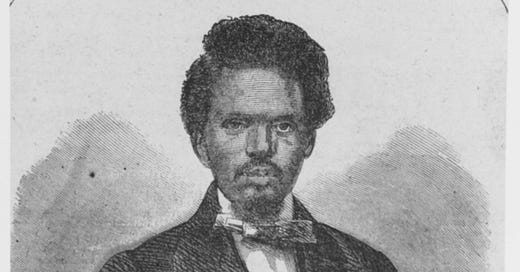

Future Congressman Robert Smalls, shown here about 1864. Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command

The Free South article does not identify the 16 delegates by race, but at least it clearly confirms a long-held claim that Smalls was chosen as a delegate to the 1864 convention. The article was written by editor James G. Thompson, a transplanted Yankee who was himself chosen as a delegate, along with his brother-in-law, Brigadier General Rufus Saxton. And while Thompson’s list contains minor misspellings of the surnames or initials of Smalls (listed as “Small”), Rivers (first initial “L.”), and Hayne (“Haynes”), there is little doubt why these three were selected—on the basis of personal courage and outstanding military service.

Future South Carolina Secretary of State Henry Hayne, shown here as a legislator. Public domain photo

South Carolina legislator and businessman Prince Rivers of Aiken County. Public domain photo

The story of how Smalls, Rivers, Hayne, and their fellow delegates may have fared in Baltimore is murky; no newspaper accounts even mention their attendance, and the party’s Proceedings nowhere mention any of their names. And confusingly, there is no real proof that Smalls even made it to Baltimore—although his official Congressional biography clearly implies he did.

His real biographer asserts that instead of going to Maryland with his fellow delegates, he was instead sent north as pilot of the USS Planter, in dire need of repairs at the Philadelphia shipyard—and was named in absentia. He had already arrived in Philadelphia days before the selection meeting was held in Beaufort.

I recently came across the Free South article as part of my ongoing research into black political participation at the Republican national conventions from 1868 to 1904, for my forthcoming book—research excerpts which I have previously published in these columns. And even though the 1864 episode technically falls outside the scope of my planned book, I found it fascinating—and now plan to use it as the basis of my introduction.

A page back in time ... is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work,

consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

* * * * * * * *

You may be wondering by now how I got interested in such an arcane subject. That’s easy. I’m a research junkie, and the more esoteric the topic, the better. Nothing satisfies this historian more than burying myself for hours—and sometimes, days—in the Library of Congress or the National Archives. And more recently, in my home office. With the advent of digitization of old books and papers and newspapers, I have worn out at least three laptop computers—and probably ruined my eyesight—in recent years.

For the last three decades, I have been researching aspects of African American political history of the late 19th century, sometimes for a constructive purpose—furthering my academic career, during doctoral studies at Union Institute & University—and beyond, publishing a number of biographies, journal articles, and historical accounts along the way. They began with George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life (2001, LSU Press)—nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in biography—and include my most recent book, Forgotten Legacy: William McKinley, George Henry White, and the Struggle for Black Equality (2020, also LSU Press).

Most of my books have dealt with the life and times of Republican Congressman George H. White, who first attracted my attention while I worked as a newspaper journalist in the 1970s in my home state of North Carolina. But I have begun to branch out in recent years to study the lives of people he knew and worked with—and in some cases, helped get appointed as postmasters while in Congress—a subject almost no one is interested in except me, believe me.

White, the only African American to serve in Congress from 1897 to 1901, was elected to two terms in the U.S. House from North Carolina’s “Black Second” Congressional District, in 1896 and 1898. He was also a delegate to two national GOP conventions in 1896 and 1900, helping nominate and then renominate William McKinley in those years.

While conducting research for my books and articles, I kept getting hooked on related but time-consuming side topics, and more than once, sidetracked indefinitely: first, by compiling a biographical directory of all black state legislators in North Carolina—more than 125 of them between 1868 and 1898, revised and updated over the last 25 years. It was followed by a second annotated list of all black North Carolinians who had attended GOP conventions after they regained the right to vote in 1868—until they were largely barred, by state constitutional amendment, from exercising the right to vote in 1902.

Next, I began expanding the scope of that N.C. list to include all black Republican delegates from the entire nation—initially from former Confederate states where most black citizens still resided until the twentieth century, then gradually from almost all other states and territories. I also compiled a thorough annotated list of all African American postmasters appointed by all Presidents from 1865 to 1900, Johnson to McKinley, along with state-by-state listings of Southern black legislators, federal appointees, and delegates to state constitutional conventions during the same period.

So I am a proud trivia nut and research nerd, no doubt about it. All these lists required a generous amount of secondary “digging” into newspaper accounts, private letters, magazines, and published books—enlarging my home library at no small expense. All while working fulltime as an editor—or at least halftime, and teaching on the side. In almost every case, it was an exhausting—as well as exhaustive—task.

Getting back to the subject at hand, however: I gradually became hooked on poring over the official Proceedings for the Republican presidential conventions in 1896 and 1900, which are widely available—and now on the computer, thankfully—and which list the names of almost all delegates who attended. Trouble is, none routinely refer to the race of the individual delegates—and guessing is just not good enough, in my book. Confirming it was more complicated.

Certain Southern states eventually began the helpful practice of inserting terms like “(Colored)” after the names in their delegate lists, as Jim Crow segregation gathered steam, even in the party of Emancipation. More often, newspaper accounts did the same thing, beginning as early as 1868 in the New York Times. A private photographic directory of most delegates in 1900 was an even more helpful tool for identifying race. But even those were sporadic, often incomplete, and sometimes just plain wrong.

Many of the delegates, like White, attended two or more conventions, making the job of recognition marginally less taxing, at least. And as my list gradually grew to include the years before White attended, I found patterns of longevity that intrigued me—and in some cases, amazed me. As with Robert Smalls, who attended nearly every single convention between 1868 and 1904, either as a full voting delegate or as an alternate, until age and infirmity stopped him from traveling after 1908.

* * * * * * *

Robert Smalls (1839-1915) was in many ways unique, in a category all his own. A technically enslaved worker with an unnamed white father, allowed for years to sell his skills on the open market, he was a tireless worker and ambitious to a fault before the War. He began buying up valuable abandoned property in Beaufort at cheap, tax-auction prices as soon as the War ended—including his old owner’s majestic home, where he and his family then spent most of the next century in residence.

Monument to Robert Smalls outside his historic home in Beaufort. Courtesy Shutterstock

And while he never truly became a man of letters—one son said Smalls could barely sign his name, and family members reportedly edited his correspondence to correct errors in grammar and spelling—he was gainfully employed to the very end, first as a very prosperous businessman, then as a legislator, congressman, and public servant. He may have been tutored while in Philadelphia, where he spent seven months in 1864, but he told one family member that he honed his reading skills by reading the Washington Evening Star during his time in Congress in the 1870s and 1880s.

Over the better part of 15 years, Smalls served all or part of five terms in Congress, first elected in 1874 and last defeated in 1888, easily becoming one of the capital’s best-known figures in the process. His increasingly rotund physique made him one of the most easily-recognized African Americans at quadrennial nominating conventions for the rest of the century and beyond, missing only the 1880 convention in an otherwise unbroken 40-year stretch as either a voting delegate or an alternate.

As the presidentially appointed U.S. collector of the port of Beaufort for nearly a quarter of a century after leaving Congress (appointed by Benjamin Harrison, serving 1889 to 1893, then reappointed by William McKinley, 1897-1913), he was also one of the nation’s longest serving black federal officials, remaining politically active until just before his death from complications of diabetes.

Robert Smalls’ pride and joy, the stolen CSS steamship Planter. Drawing courtesy American Battlefield Trust

In 1864, when he was selected to attend the Baltimore convention, he was still just 25 years of age, but had already gained a fearsome reputation for shrewdness and daring—for exploits in leading the squadron blockading Charleston’s harbor, and an unusually high measure of social standing for a man so recently enslaved.

“In April of 1864, Smalls and his wife Hannah hosted, in their new mansion, the wedding of Lavinia Wilson, a formerly enslaved woman who had escaped on the Planter, to a soldier in the 33rd United States Colored Troops. In attendance was the military governor, General Rufus Saxton, and his staff,” according to one local report.

When discharged from the Union Navy in 1865, he had already piloted or captained vessels in 17 sea battles, and gained the respect of many. During the seven months he spent in Philadelphia, awaiting the return of his treasured ship, he was cited for violating the city’s strict racial segregation of its streetcars—his punishment being tossed off the streetcar, with his white companion—and responded by walking miles to his destination, thus helping initiate the three-year boycott which ended that practice in 1867. [Sample highlights of his life in the excellent 1995 biography penned Edward A. Miller Jr. (Gullah Statesman: Robert Smalls from Slavery to Congress, 1839-1915, University of South Carolina Press).]

The text of his official Congressional biography, written decades after Smalls’ death, occasionally incorporates small details more legendary than factually sound: for instance, “He joined free black delegates to the 1864 republican national convention, the first of seven total conventions he attended as a delegate.” (See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CDOC-108hdoc224/pdf/GPO-CDOC-108hdoc224-2-2-16.pdf. )

As Miller’s more carefully-researched biography concludes, Smalls actually remained in Philadelphia during the entire time of the two-day Baltimore convention (June 7 and 8). While he was close enough, theoretically, to make the trip by train, and might easily have obtained leave to do so from General Saxton, himself a delegation member—Smalls was doubtless preoccupied by his primary naval duties in overseeing the expensive repairs to his precious ship, which would have begun in late May.

Editor James G. Thompson, among the 16 members of the ill-fated delegation, briefly described their experience in a subsequent edition of his Free South newspaper (July 2, 1864): “Many distinguished citizens from all sections of the Union called upon different members of our delegation”—perhaps intrigued by the spectacle of the South Carolina flag flying over Guy’s Hotel, as he noted—“and great interest was manifested in the work of reorganization in South Carolina.” (Guy’s Monument Hotel, facing the Baltimore Battle Monument on Calvert Street, did not house other major delegations, according to newspaper accounts.)

Thompson does not mention whether the race of his delegates caused any difficulties in their registration, but then Baltimore was somewhat more relaxed about racial segregation than other U.S. cities. It was home to the largest population of free blacks of any northern city, outnumbering its small number of black slaves by 8 to 1.

According to Wikipedia, “Despite the overall poverty of the city's free black people, compared with the condition of those living in Philadelphia, Charleston, and New Orleans, Baltimore was a ‘city of refuge,’ where enslaved and free black people alike found an unusual amount of freedom.” [Also see “Social justice and Baltimore: A brief history,” 2017, https://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/9603/10994 .]

Guy’s Monument Hotel (left) —minus South Carolina flag—as it looked 30 years later. Courtesy Enoch Pratt Free Library

But the Beaufort delegation’s trip, while symbolically important, was for naught, essentially. They were given seats within the convention, but gained no other rights; their hopes of bringing the question of Negro suffrage onto the convention floor were dashed when the chair decided not to recognize them as official delegates.

Smalls’ biographer attributed the chair’s rejection of their claim to the fact that the Beaufort delegation pretended to represent the entire state of South Carolina—an obvious fallacy, since almost all of the Confederate state where the war had begun in 1861 was still actively at war with the rest of the Union. Like the occupied portions of Virginia—whose bid was also refused, despite having sent a delegation four years earlier—occupied South Carolina was deemed not yet ready to have convention voting rights restored. Occupied Florida was overlooked, as well.

Thompson himself seemed to blame racial prejudice at the highest party levels for the exclusion: “All were ready to have the Negroes fight for the Union, die for it, but were hardly ready to have him vote for it.” But he nonetheless sensed an important future ahead for South Carolina, saying philosophically that “We could afford to wait” for the 1868 election, and he himself proved it by his own remarkable career in that era.

Other Southern state delegations—representing the far larger Union-occupied portions of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee—made far stronger cases to the convention, and were acceptable in 1864. But none of them had dared to risk sending black delegates. Even without Smalls in the room, the very noticeable uniformed presence of delegate Prince Rivers (or even the very light-skinned Henry Hayne)—and perhaps three or four black alternates, including Sergeants Henry “Harry” Williams and Edward Colvin—would easily have caught the eyes of party officials, many not yet wedded to the notion of black suffrage nationwide.

Sgt. Henry Williams, alternate SC delegate to the 1864 convention. Courtesy Find a Grave

Even though limited to slaves in states in rebellion, like South Carolina, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation a year earlier had still not become universally popular, foreshadowing the strong possibility of eventual suffrage for freed slaves. At this convention a year later, Republican-leaning border states with significant slave populations—such as Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri—and others did not welcome the image of black voters any time soon.

* * * * * * * *

There appears to be no way to document which of the 16 Beaufort delegates—four at large, and 12 “representing the State [of South Carolina]” plus 16 corresponding alternates, both white and black, actually made the sea trip from Port Royal to Baltimore, which took up to a week. But it still seems highly likely that Rivers and Hayne were among the group, perhaps even accompanied by General Saxton.

Rivers (1824-1887), born enslaved, was a singularly impressive soldier, later drawing strong praise for his performance and ability from Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, his white commanding officer, in his 1869 memoir (Army Life in a Black Regiment).

Sergeant Prince Rivers, our color-sergeant, who is provost-sergeant also, and has entire charge of the prisoners and of the daily policing of the camp. He is a man of distinguished appearance, and in old times was the crack coachman of Beaufort…. They tell me that he was once allowed to present a petition to the Governor of South Carolina in behalf of slaves, for the redress of certain grievances; and that a placard, offering two thousand dollars for his recapture, is still to be seen by the wayside between here and Charleston.

He was a sergeant in the old "Hunter Regiment," and was taken by General [David] Hunter to New York last spring, where the chevrons on his arm brought a mob upon him in Broadway, whom he kept off till the police interfered. There is not a white officer in this regiment who has more administrative ability, or more absolute authority over the men; they do not love him, but his mere presence has controlling power over them. He writes well enough to prepare for me a daily report of his duties in the camp; if his education reached a higher point, I see no reason why he should not command the Army of the Potomac.

He is jet-black, or rather, I should say, wine-black … His features are tolerably regular, and full of command, and his figure superior to that of any of our white officers,—being six feet high, perfectly proportioned, and of apparently inexhaustible strength and activity. His gait is like a panther's; I never saw such a tread. No anti-slavery novel has described a man of such marked ability. He makes Toussaint perfectly intelligible; and if there should ever be a black monarchy in South Carolina, he will be its king.

Higginson left Port Royal weeks before the delegate selection, and did not mention it in his memoir [available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6764/6764-h/6764-h.htm#link2H_APPEb ]. General David Hunter is often best remembered for his infamous emancipation order—quickly rescinded—for slaves in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida, which predated Lincoln’s proclamation [see his biography at the National Park Service website, https://www.nps.gov/people/general-david-hunter.htm ].

After the War, Rivers went on to a remarkable career as a businessman, state legislator, and public servant, helping found Aiken County in the state’s western region and serving as a state legislator from 1868 to 1873, after attending the state’s constitutional convention in 1868. He later became a judge. [His National Park Service biography is available at https://www.nps.gov/people/prince-rivers.htm .]

His comrade in arms, Sergeant Henry E. Hayne (1840-1898?], drew only a passing mention from Higginson—as one of two state legislators from his ranks—but also served in an equally distinguished capacity as a public servant in postwar South Carolina. A rare freeborn mulatto among the ranks of the 33rd USCT, he was well educated by his white father and free black mother in Charleston—and “passed for white,” some say, well enough to enlist in the Confederate Army before “defecting” to the Union side in mid-1863.

After being mustered out in 1866, he represented Marion County in the state Senate from 1868 to 1872, served as principal of a school for black students, and was also a delegate to both the 1868 constitutional convention and the 1868 Republican national convention—before becoming South Carolina’s elected Secretary of State in 1872. During his five-year term, he also became the first black student to enroll at the University of South Carolina campus in 1873. [His full South Carolina Encyclopedia biography appears at https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/hayne-henry-e/ .] .]

For both men, the “Port Royal” experiment—described by some historians as a dry-run rehearsal for Reconstruction—paid handsome dividends. Much of the credit for the success of Port Royal—in which black civilians, or contrabands, lived as free citizens under careful white supervision—must go, however, to General Rufus Saxton, who recruited Higginson as commanding officer of the 33rd USCT, and who groomed his future brother-in-law, editor Thompson, for his own career in South Carolina politics.

Next time: The Port Royal experiment casts a long shadow over postwar South Carolina