African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 8: In 1880, Chicago becomes the default setting for the Republican convention

My last entry described an increasing level of activity by African American delegates at the 1880 Republican presidential nominating convention in Chicago, which would now become the most frequent gathering point for the quadrennial GOP convention. It would meet there for all but three of its next 10 sessions (Minneapolis in 1892, St. Louis in 1896, Philadelphia in 1900).

In 1880, the setting was the city’s gigantic Interstate Exposition Center, built almost a decade earlier. Its attractive lakefront Michigan Avenue site was certainly a major factor in convincing Republican leaders to select Chicago, and indeed, its seating capacity—at least 10,000—made it a major tourist attraction, with 40,000 would-be attendees still unable to gain admission.

Chicago’s Interstate Exposition Center, home to 1880 GOP convention. Photo courtesy Chicago Historical Society

According to the New York Times, delegates at the Exposition Center were reminded of the nation’s two most revered leaders by huge portraits of the first President, George Washington, overhead, and the first Republican President, “the martyred [Abraham] Lincoln,” along the rear wall, dividing a banner bearing a mildly-misquoted quotation from Lincoln’s Gettysburg address— “And that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall never [sic] perish from the earth."

According to the same journalist, “a host of prominent men were seen. White alternated with black, as the colored men sat side by side with the white representatives of the great party which had freed them from slavery. A leader of these colored men was Blanche K. Bruce, who has reached the high honor of a seat in the United States Senate. Every one of these dark faces glowed with intelligence and a deep and thoughtful interest” in convention actions.

Interior photograph of the 1880 Chicago convention. Photo courtesy New York Times

Besides Bruce, the Times correspondent sighted Frederick Douglass, currently U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia, a non-delegate. Among notable black leaders not named by the Times were five former U.S. congressmen—Alabama’s James T. Rapier and Benjamin S. Turner, Georgia’s Jefferson F. Long, and South Carolina’s Robert Brown Elliott, all delegates; and alternate delegate John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, who took an active part in proceedings. (It is not certain whether ex-congressman Joseph H. Rainey, an alternate delegate, attended.)

For the first time since 1868, no black delegate or alternate served in the U.S. House of Representatives; when Senator Bruce’s term ended in January 1881, the Congress would soon lack any black representation. Now-familiar faces were also missing from the official 1880 rolls: South Carolina’s Robert Smalls, a former congressman, a delegate from 1868 to 1876, and onetime Louisiana governor Pinckney Pinchback, who had created a stir among his 1876 delegation by denouncing President Grant. Both returned to Chicago in 1884.

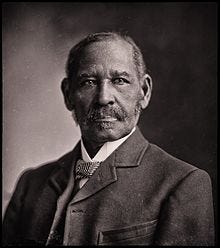

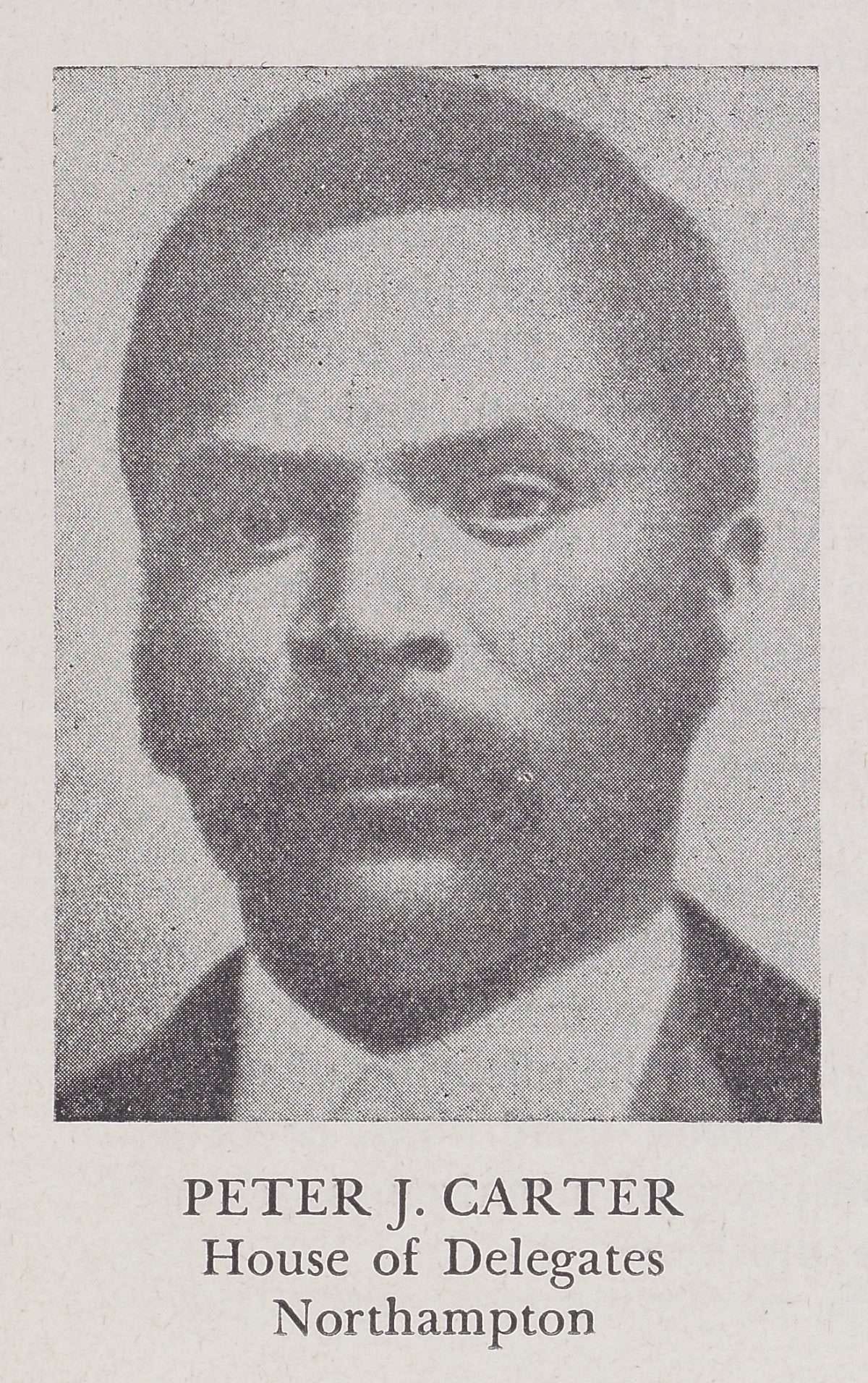

But in some states, other black delegates were now veterans. Arkansan Mifflin Gibbs; Georgia’s Elbert Head, Madison Davis, and Edwin Belcher; Virginia’s Peter J. Carter; and North Carolina’s James H. Harris each attended their third straight convention.

Arkansas delegate to 1880 convention, Mifflin W. Gibbs (1823-1915). Public domain photo

Georgia delegate to 1880 convention Madison Davis (1823-1902). Public domain photo

Virginia delegate to 1880 convention Peter J. Carter (1845-1886). Photo courtesy Encyclopedia Virginia

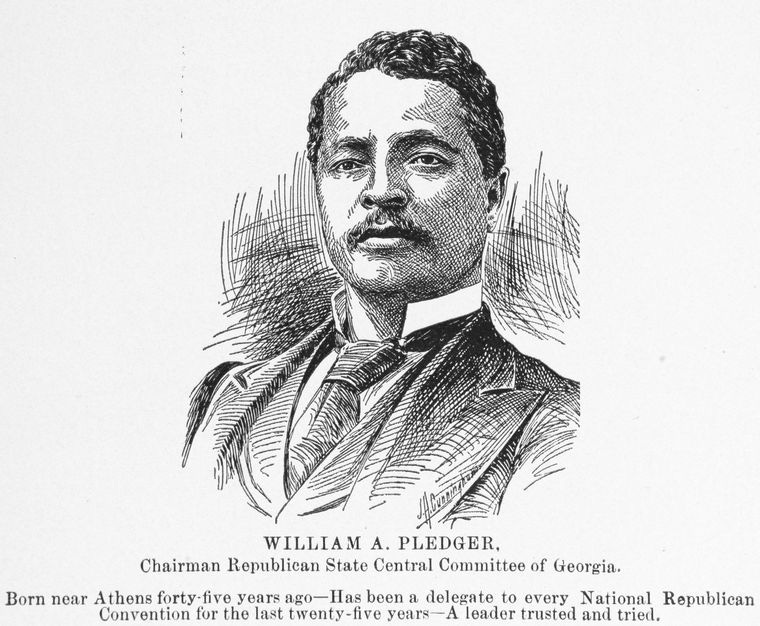

Georgia’s James B. DeVeaux and Texan Norris Wright Cuney were notable second-timers. New first-time delegates destined as familiar faces were Columbia, South Carolina, postmaster Charles Wilder; Georgia lawyer and journalist William Pledger, state party chairman; and Jacksonville attorney Joseph Lee, longtime Florida party secretary.

Texas delegate to 1880 convention Norris W. Cuney (1846-1898). Public domain photo

William A. Pledger (1852-1904), Georgia delegate to 1880 convention. Illustration courtesy Schomburg Center, NYPL

And among the 56 black alternates chosen in 1880— some of whom may have attended the convention as observers—were four with unique careers ahead, most far from home. South Carolina’s Thomas E. Miller, a lawyer and state legislator, would serve a partial single congressional term in 1890-1891; after his 1890 defeat for reelection, he would become president in 1896 of the school now known as South Carolina State University.

Future Congressman Thomas E. Miller, South Carolina alternate delegate in 1880. Public domain photo

The rest made their names known better elsewhere. For instance, Thomas A. Sykes, a Nashville, Tennessee, legislative candidate, had served previously as a two-term state legislator in North Carolina, which he represented as an 1872 delegate. After his 1880 election, Sykes served one term in the Tennessee General Assembly, one of the rare black legislators in two different states.

David Augustus Straker (1842-1908), of Orangeburg, South Carolina, would later become far better known as the first black lawyer to appear before the Supreme Court in Michigan, where he moved after visiting Detroit in 1885. The Barbados native emigrated to the United States as a schoolteacher in Kentucky in 1866, then studied law at Howard University, before practicing law with ex-congressman Robert Brown Elliott.

D. Augustus Straker, Barbados-born delegate in 1880 from South Carolina. Public domain photo

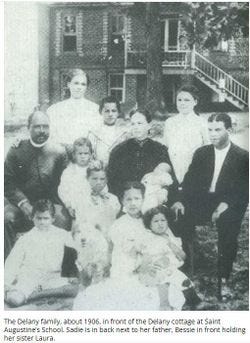

The Rev. Henry B. Delany (1858-1928) [also spelled Delaney], from largely-black Fernandina, Florida, would achieve his greatest fame as the first African American to be elected Bishop Suffragan of the Episcopal Church. In 1881, Delany’s local parish sponsored his education at all-black Saint Augustine’s Episcopal college in Raleigh, North Carolina, whose faculty he joined after graduating in 1885; he then became a Raleigh parish priest in 1895.

Named suffragan bishop by the Diocese of North Carolina in 1918, his career was impressive enough, if largely forgotten. But his 10 children all graduated from college—and carried on his legacy in distinctive ways.

Family of 1880 convention alternate Henry B. Delany (left), ca. 1908. Photo courtesy Find a Grave website

Decades after his death, oldest daughters Sadie and Bessie, educators and civil rights activists, became worldwide sensations as centenarian authors of the best-selling dual autobiography, Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters’ First Hundred Years, published by Dell/Random House in 1993.

* * * * * *

The 1880 convention selected many black delegates for important positions, including three on the Credentials Committee: attorneys, Florida’s Joseph E. Lee and Georgia’s Edwin Belcher; and North Carolina’s George W. Price Jr., a businessman and legislator. In addition, two black delegates served on the Committee on Resolutions: Samuel H. Holland (1844-1886) of Arkansas and North Carolina’s James H. Harris.

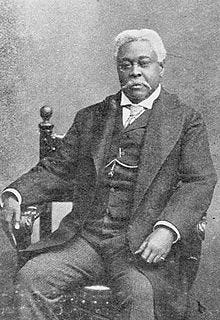

Six black delegates served on the Committee on Permanent Organizations: Benjamin S. Turner (Alabama); John F. Cook (District of Columbia); Madison Davis (Georgia); James Hill (Mississippi); William J. Whipper (South Carolina); and H. Clay Harris (Virginia).

Rules Committee members included Alabama’s John A. Thomasson ; John H. Johnson (Arkansas); James Dean (Florida); Hannibal Caesar Carter (Mississippi); and Charles M. Wilder (South Carolina). Black delegates from four states became convention vice presidents: Dr. Henry Jerome Brown (Maryland); U.S. Senator Blanche K. Bruce (Mississippi); lawyer William F. Myers (South Carolina); and William H. Holland (Texas), an alternate delegate in 1876.

Dr. Henry J. Brown (1830-1920), Maryland delegate to 1880 convention. Courtesy Maryland State Archives

William H. Holland (1849?-1907), Texas delegate to 1880 convention. Courtesy Austin Public Libraries

Chosen as state assistant secretaries were black delegates George W. Washington of Alabama; Edward I. Alexander (Florida); George Washington Gayles (Mississippi); Israel B. Abbott (North Carolina); and William A. Hayne (South Carolina).

* * * * *

The final task awaiting 1880 delegates was serving on a committee to announce their formal nominations to James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Black delegates from four states included three members well-known nationally: ex-judge Mifflin Gibbs of Arkansas, and ex-congressmen Jefferson F. Long (Georgia) and Robert Brown Elliott (South Carolina), who had once served in the U.S. House with Garfield.

Joining them on this committee was a less widely-known North Carolina legislator, Stewart Ellison of Raleigh, a master carpenter who had just completed his third term in the N.C. General Assembly and a decade on the Raleigh City Council.

In most cases, two committees were needed, each to visit the presidential and vice-presidential nominees at their homes after the convention. In this unusual year, because both nominees were delegates in Chicago, the joint committee received them at a special ceremony in Chicago’s nearby Grand Pacific Hotel.

Next time: Tribute to a rare person, lost too soon: Dulcie Murdock Straughan