African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 11: Back to work in 1888, as Republicans seek to unseat Cleveland

The 1888 Republican convention was an unusual political experience in many ways—both for party leaders and the rank and file, as well as the first convention held nearly outdoors. It was the first time since 1860 that Republicans convened as a party without holding the White House. There were few former leaders left to guide the party as it sought to regain the presidency; only one former Republican president—the estimable Rutherford B. Hayes—and one former vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, were still alive, although both had retired and neither attended the 1888 gathering.

The party’s last president, Chester Arthur, had died in 1886, just a year after leaving office; his predecessor, James A. Garfield, of course, had died in office in 1881. In 1885, the revered Ulysses Grant, a former two-term president, had also died. Its last vice presidential nominee, Senator John A. Logan, and two former vice presidents, Schuyler Colfax and William A. Wheeler, had all died since the last convention in 1884.

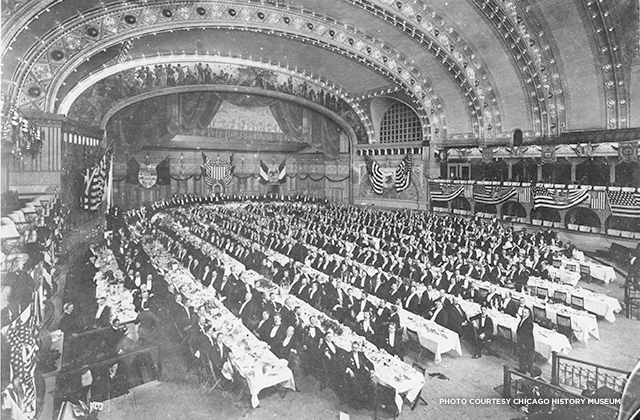

Interior of Chicago Auditorium Building’s theater. Courtesy Chicago History Museum

When the convention convened in Chicago in June 1888, there was still no roof over the huge theater; convention organizers were forced to drape an enormous tarpaulin over the building for the duration of the convention.

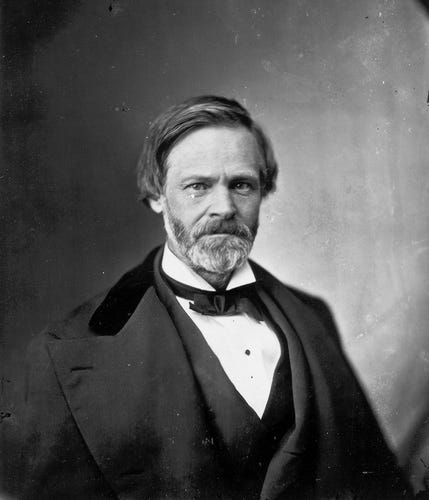

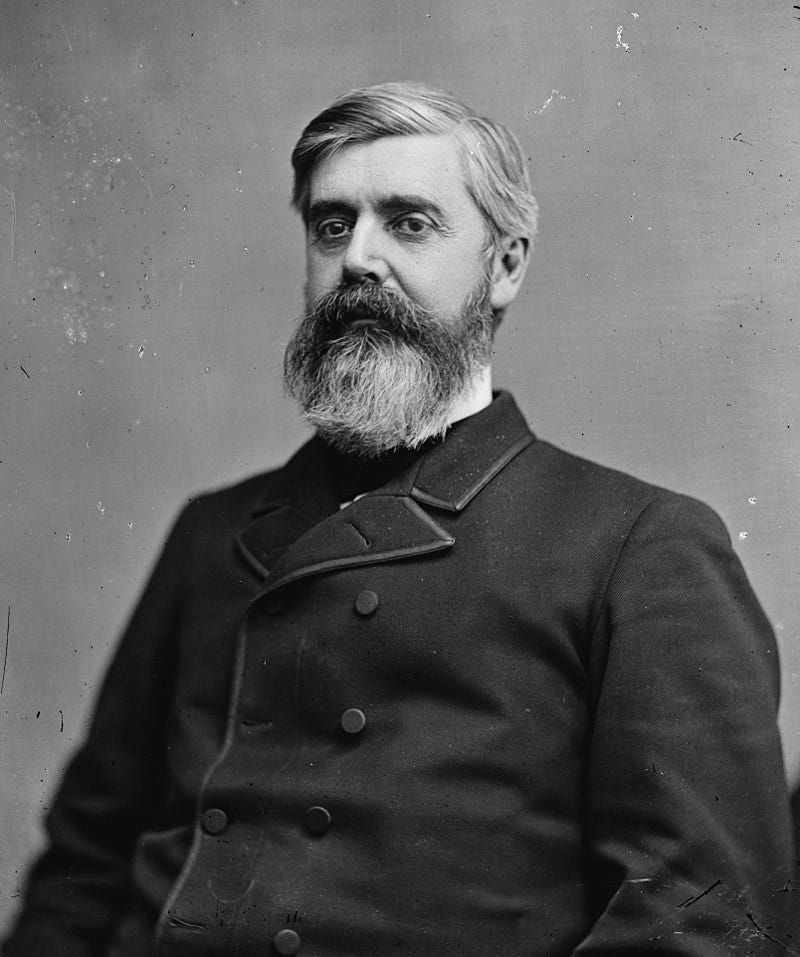

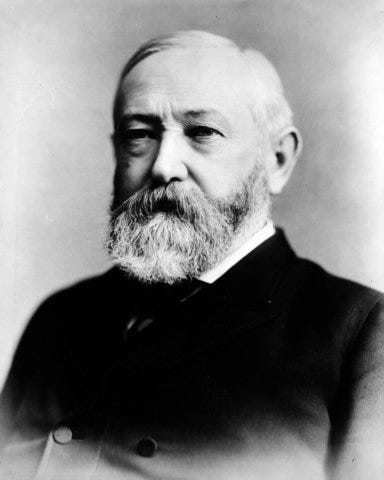

There was also no front-runner, with a bitter fight predicted for the nomination. Perennial candidate James G. Blaine, who had lost narrowly to Cleveland four years earlier, chose not to seek renomination. At least six major candidates were set to compete, including Senator John Sherman of Ohio—the favorite of many black delegates; federal Judge Walter Gresham, the former Treasury Secretary under Arthur; and former Ohio Senator Benjamin Harrison. The balloting stretched into eight ballots, necessitating a six-day run for what was planned as half that long.

Senator John Sherman of Ohio, ca. 1888. Courtesy U.S. Senate Historical Office

Former Treasury Secretary Walter Gresham, ca. 1888. Public domain photo

Former Senator Benjamin Harrison, ca. 1888. Public domain photo

John Lynch, the Mississippi delegate who had served as temporary chairman in 1884, was among the most experienced of least 61 black delegates in attendance—a 10 percent drop from the 1884 total (68). About half of the black delegates had previously served either as delegates or alternates, while two states—Missouri and West Virginia—sent their first black delegates in 1888. Future Congressman John Mercer Langston of Virginia, who had delivered addresses outside the halls of many previous conventions, was among the new delegates, selected after his nomination for Congress that same year.

Future Congressman John Mercer Langston, Virginia delegate in 1888. Public domain photo

Noticeably absent in1888, however, was former Senator Blanche K. Bruce, a veteran delegate fallen victim to an internal party squabble recounted by Lynch in his autobiography: “He was not only seriously disappointed but very much incensed at Mr. [James C.] Hill’s action in having [Thomas] Stringer instead of himself elected a delegate,” leading to a permanent estrangement between Bruce and Hill. The former Register of the U.S. Treasury would at least have the last laugh at the convention on his state nemesis—receiving 11 votes for vice president, seven of them coming from Mississippi.

Bruce, already a millionaire plantation owner, was at least able to support himself during the interregnum, But others, particularly rank-and-file party members, had been in virtual limbo for nearly four years. Patronage jobs which had been awarded almost exclusively to party members for two decades, between 1861 and 1885, had all but dried up.

The loss was most acute for black party members in the South, who had once been leading candidates for appointments to low- and mid-level federal jobs under Presidents Grant, Hayes, Garfield, and Arthur. While they still retained limited influence in state parties with large black memberships—particularly in the Carolinas, Florida, Georgia, Texas, and Virginia—they had few allies left in Congress.

The party’s last two black representatives, North Carolina’s James E. O’Hara and South Carolina’s Robert Smalls, had been defeated in 1886, leaving the U.S. House without a black member for the first time since 1870. Republicans still narrowly controlled the U.S. Senate, but Democrats had held onto the House in 1886—with 92 Democrats and just nine Republicans elected from the 11 former Confederate states (six from Virginia, two from Tennessee, and one from North Carolina).

With few champions in Congress, Southern Republicans faced a losing battle in patronage, particularly in appointments of postmasters. In previous years, black postmasters were often selected as delegates or alternate delegates to the party’s national conventions: in 1884 alone, three delegates (Georgia, 2, and South Carolina) and two alternate delegates (Florida and Mississippi) were drawn from the ranks of 38 appointments during the Hayes, Garfield, and Arthur administrations.

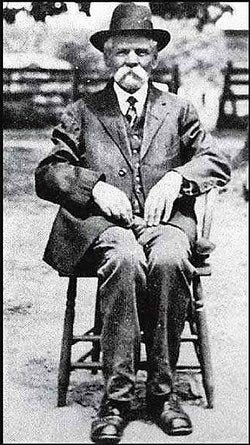

South Carolina delegate Paris Simpkins, lawyer and former postmaster, in 1888. Public domain photo

Beginning in 1885, the Cleveland administration all but halted appointments of new black postmasters—selecting just two black postmasters in four years—and only a handful of black Democrats for any federal positions at all.

In 1888, three of the five delegates and alternate delegates who had attended while serving as postmasters in 1884—Georgia’s J. Curt Beall and Madison (Matt) Davis, and Paris Simpkins of Edgefield, South Carolina, were back, if now as “civilians.” For the first time in recent history, no black delegate or alternate was still serving as a postmaster anywhere, all having been replaced by Cleveland with white Democrats when their terms expired.

* * * * * * * *

Delegates in Chicago in 1888 were meeting for the first time at a new site, the still-unfinished Auditorium Building off Michigan Avenue. Inspired by the Richardson Romanesque style of architect Henry Hobson Richardson, the building was designed by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan, and was completed almost a year after the convention met.

Exterior of Chicago’s Auditorium Building, ca. 1890. Pubic domain photo

Despite its opulence, a New York Times correspondent’s description (“The Hall and Its Arrangement,” June 20) of the scene was somewhat less than flattering: “Its size was impressive, but the absence of windows, the exclusion of daylight, added to the resort on electrical illumination, and through the effect upon the imagination to the distressing heat. The air was stifling and hot, and fans did but little to mitigate the discomfort. Away up in the hot gallery a hundred feet aloft—it must be 100 degrees if it is anything in the shade.” At least the acoustics were good, “and the audience [can] hear the speeches much more easily.”

Next time, delegates struggle to decide on a candidate.

Next time: Picking a candidate proves tricky, across eight ballots