African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 3: Helping to renominate President Grant in Philadelphia in 1872

Last time, readers learned more about the details of the Chicago Republican convention of 1868, the first time that African Americans took part in the nomination process as delegates, representing eight of the former Confederate states.

This week, I will take readers on a quick tour of the 1872 Republican convention in Philadelphia, which took place during the first week of June and was attended by nearly five times as many black voting delegates—55 out of 752 total, compared to just 12 blacks in 1868—with four times as many alternates (at least 48 identified so far, up from 12 in 1868).

The American political landscape had changed remarkably in just seven years since the end of the Civil War, whose legacy had so recently given 4 million black slaves legal freedom and led to passage of the Reconstruction Amendments granting them full citizenship, enabling them to vote and hold public office.

For the first time in U.S. history, a handful of these black delegates either already held high public office—both in their home states and in Washington—or were now running for office, making them rising power brokers within their party.

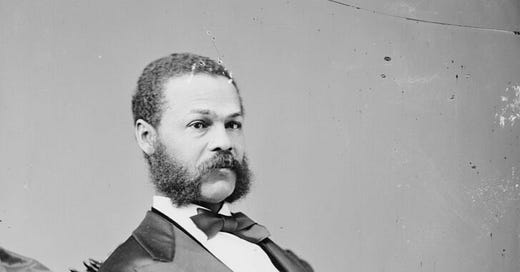

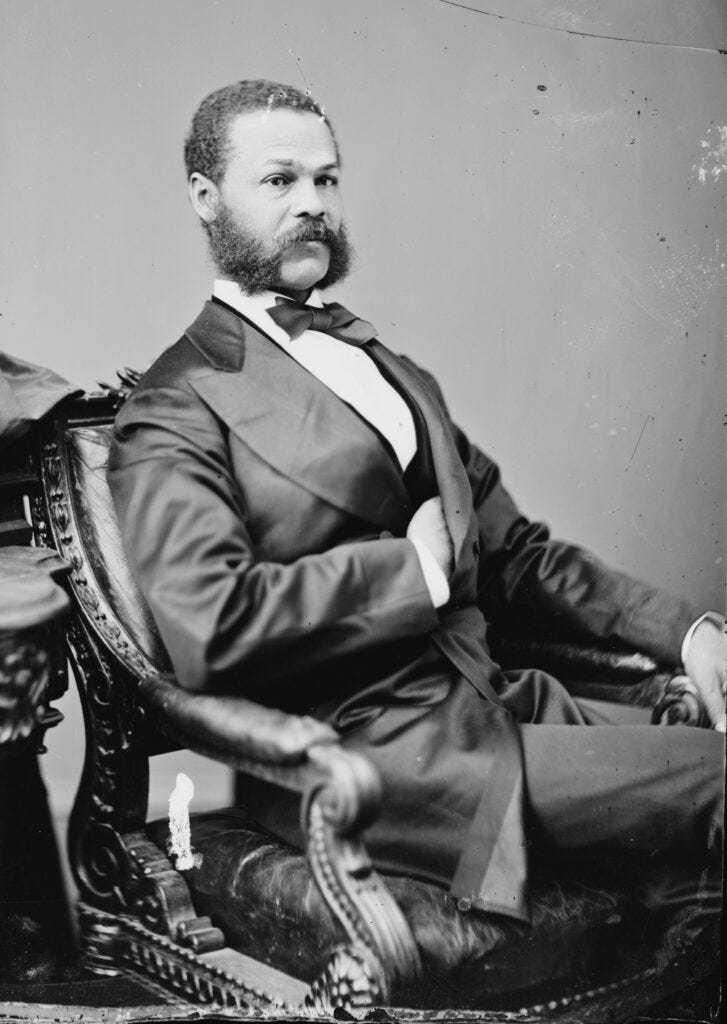

Among the black delegates and alternates in 1872 were two sitting members of Congress, South Carolina’s Robert Brown Elliott and Florida’s Josiah Walls; one former congressman, Jefferson Long of Georgia; and no less than seven future black members of Congress. In addition, two sitting lieutenant governors (Louisiana’s Pinchback and South Carolina’s Alonzo Ransier, currently campaigning for Congress), the Speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives (John Roy Lynch, also a Congressional candidate), and two sitting secretaries of state (Mississippi’s James Lynch and South Carolina’s Henry Hayne) were among their state delegations.

Georgia’s Jefferson F. Long, who served in Congress from 1870 to 1871. Public domain photo

South Carolina’s Robert Brown Elliott, who served in Congress from 1871 to 1874. Public domain photo

Florida’s Josiah T. Walls, who served in Congress between 1871 and 1876. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Soon-to-be South Carolina congressman (1873-1875) Alonzo J. Ransier, Photo courtesy Library of Congress

It was oddly appropriate that Philadelphia become the first real showcase for America’s politically active black population. The city already held a black population exceeding 30,000 in 1870—up from 22,000 free blacks recorded a decade earlier, the largest single population of black Americans outside the Southern states. “Most lived in South Philadelphia near what is today Center City ... They came because of Philadelphia's reputation as a thriving political, cultural, and economic center for African Americans,” according to the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, noting that many black residents had served in 11 Union Army military regiments organized after passage of 1862 legislation allowing blacks to enlist.

As in most other northern cities, actual political participation locally had begun much more recently—triggered only by the 1870 passage of the Fifteenth Amendment—but before that, Philadelphia’s black citizens had begun organizing successfully to fight racial segregation on city streetcars in 1867, for instance. While decades would pass before a black was elected to represent Philadelphia in the state legislature (Harry Bass, 1910), black voters had quickly became influential in state Republican politics, with the selection of the state’s first black alternate convention delegate as early as 1892 (Andrew Stevens).

By the time the convention opened in early June 1872, party leaders in at least 15 states and the District of Columbia had begun sending blacks as delegates or alternates. Not surprisingly, by far the single largest state pools for those selections consisted of current or former members of the respective state legislatures: at least 61 delegates or alternates from 10 states—all but Maryland, Missouri, New York, Ohio, and Tennessee—were either sitting members of or had already completed a term in their legislatures.

* * * * * *

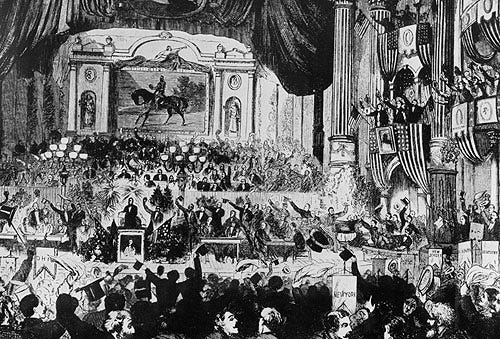

Philadelphia’s Academy of Music, site of the 1872 GOP convention. Public domain illustration

The New York Times correspondent all but gushed over the decorations planned for the extravagant interior of the Philadelphia Academy of Music in a front-page article published three days before the convention opened. A day later, the Times began describing the arrival of state delegations, taking pains to identify certain delegates as “colored,” among them South Carolina’s lieutenant governor, Alonzo Ransier; congressmen Josiah Walls (Florida) and Robert Brown Elliott (South Carolina); Louisiana’s P. B. S. Pinchback, the state’s lieutenant governor; William F. Butler, a “prominent colored man of New York City,” and Ohio’s J. Madison Bell, along with two otherwise-unnamed delegates (out of seven) from Virginia.

All in all, the Times correspondent counted just “twenty of their most prominent and capable men, some of whom will be conspicuous in the proceedings of the body.” (This was fewer than half the actual number of black delegates.) Black delegates “unanimously demand him [Grant] as the favorite of their people,” according to the article.

Non-elected black officials included Butler, a Canadian-born minister now serving a New York City AME church, who had helped found the Negro Republican Party in Kentucky in 1867, and Ohio’s Bell, a poet who had gained regional renown for his 1868 satire mocking then-President Andrew Johnson, titled “Modern Moses, or ‘My Policy’ Man.” (See https://poets.org/poet/james-madison-bell/ .)

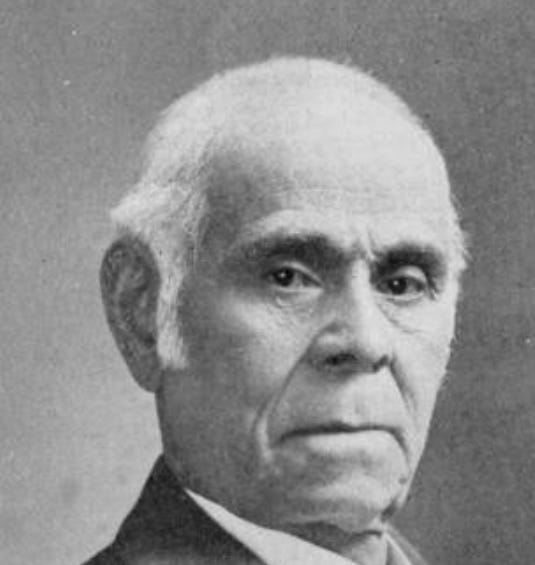

J. Madison Bell (1826-1902), poet and 1872 Ohio delegate to GOP convention. Photo courtesy New York Public Library

Among future members of Congress in attendance, in addition to Ransier, were North Carolina’s John A. Hyman; Alabama’s Jeremiah Haralson; South Carolina’s Robert Smalls and Richard Cain; and Mississippi’s John Roy Lynch, in addition to Mississippi’s future U.S. Senator, Blanche Kelso Bruce.

Blanche K. Bruce, Mississippi alternate delegate in 1872, became a US Senator in 1875. Public domain photo

John Roy Lynch, Mississippi alternate in 1872, was elected to US House later that year. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Nearly two dozen of these black leaders had already made history by serving as delegates to their respective state constitutional conventions, particularly in South Carolina, where a majority of delegates were black—including five delegates to this convention and five alternates—and North Carolina, which sent three such delegates and two alternates to this convention.

The growing respect accorded by the national party to its Southern black leaders was reflected in the makeup of the key credentials committee, to which black delegates from five states were named (Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Virginia); the rules committee (Georgia); the resolutions committee (North Carolina and South Carolina); and the committee on permanent organizations (South Carolina and the District of Columbia).

South Carolina’s Ransier was named chair of his state’s executive committee, while Virginia’s Charles Malord and John Cooke of the District of Columbia were vice president of their committees. Black delegates were named as secretaries of their state executive committees in Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas.

But the strongest indicator, perhaps of the party’s regard for its black delegates in 1872 was borne out by the number of times black delegates were asked to address the convention. Black delegates from four states—Arkansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina—each gave impassioned speeches on the convention’s first day, and were roundly applauded.

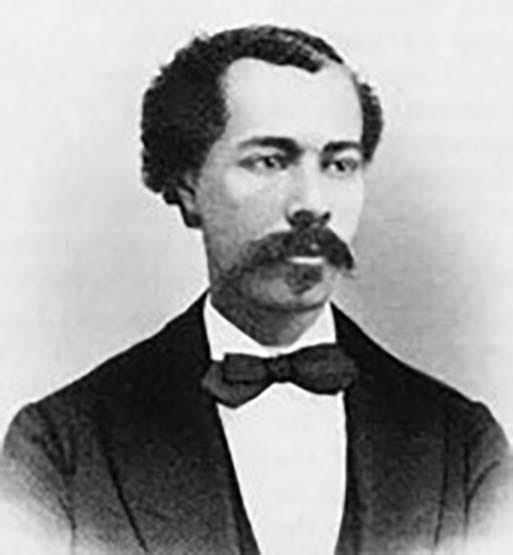

William H. Grey of Arkansas, first black delegate to address the 1872 GOP convention. Public domain photo

In his alternately humorous and serious remarks, Arkansas delegate William H. Grey (1829-1888) became the first black delegate ever to address a national convention. Born free in Washington, D.C., he was already a successful businessman in postwar Arkansas when he attended that state’s 1868 constitutional convention. According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, Grey “emerged from the [1868] convention with the reputation of an elegant, outstanding speaker capable of transmitting deeply held emotions through his words.”

The ordained AME minister recalled his presence in Chicago in 1868, when President Ulysses Grant had first been nominated, and pleaded for passage of a national Civil Rights bill. Just 43 at the time of this speech, he seemed somehow older and wiser than many of his black colleagues, an elder statesman adopting a philosophical tone:

“Words fail me, upon this occasion, to thank you [for your willingness] to listen not only to the greatest of her orators, but to the humblest citizens of this great Republic … We stand, many of us, in a prominent position in the Southern States, but right among the people where we hold these positions, the law is so weak and the public sentiment so perverse that the common civilities of a citizen are withheld from us.

“We want the Civil Rights bill. We ask of the American people as the natural result of their own action that we shall be respected as men among men and as free American citizens. … All we ask is a fair chance in the race of life. Give us the same privileges and opportunities that are given to other men.”

His full text, reprinted below, is well worth a closer reading.

For all of Grey’s profound, measured words, it was the three speeches from his more youthful colleagues that best foreshadowed the promising future for black Republicans: Mississippi’s youthful Secretary of State, James D. Lynch, 33, touted by many as the next member of Congress from that state: sitting congressman Robert Brown Elliott of South Carolina, still just 30; and North Carolina’s James H. Harris, 40, whose turbulent career as both state legislator and perennial, if unsuccessful congressional candidate would last the longest, for another two decades.

Next time: Three spirited speeches set the pace for the future of black Republicans