African Americans enter the nation's political game

Part 6: The Cincinnati convention betrays small fissures in black solidarity

Last time, I began describing the June 1876 national Republican convention, held in Cincinnati, and its significant number of African American delegates, as part of a series of excerpts from my planned book on the subject of black participation in the presidential nominating process after the end of the Civil War.

This week, I will take a look at the beginnings of disagreements among those black delegates on the choice of a Republican presidential nominee, based on my continuing research into the subject, including both official proceedings of the convention, newspaper articles in leading U.S. newspapers of the era, and other resources.

Interior of the huge Cincinnati Exposition Center, built in 1870. Courtesy Frank Leslie’s IIlustrated Newspaper

The choice of Cincinnati had been a mildly controversial one for the 1876 convention. The Exposition Hall itself had played host to the splinter Liberal Republicans’ national convention in 1872, at which Horace Greeley had been nominated to oppose President Grant’s bid for a second term. As described in the New York Times, the “hall in which the Convention assembled this morning [June 14] is an immense frame structure with a seating capacity of least 7,000,” more than four times the number of attendees, but with surprisingly good acoustics.

The city itself, just across the Ohio River from formerly slaveholding Kentucky, still flirted with segregationist practices, despite the 1875 Civil Rights Act, which forbade discrimination against citizens in public accommodations on account of race.

According to Wikipedia’s article on that legislation, “the act was designed to ‘protect all citizens in their civil and legal rights,’ providing for equal treatment in public accommodations and public transportation and prohibiting exclusion from jury service”—provisions which would be resurrected a century later in the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But its unpopularity and President Grant’s apparent misgivings about the overall bill, enacted in March 1875, had led to it being enforced only sporadically. (It would be declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1883.)

And while there is no overt mention in newspaper articles of black delegates being turned away from any of the Cincinnati hotels used by state delegations, racial segregation had been routinely practiced by some city hotels in recent years. Ohio’s future Congressman William McKinley, for instance, made no secret of simply refusing on principle to patronize any Cincinnati hotels which did not accept black guests during his time in Congress (between 1877 and 1891). Not yet in office, McKinley was not an 1876 convention delegate, though he was an ally of eventual nominee Rutherford Hayes, and may well have attended as an observer.

Nor did the 1876 Ohio delegation appear to have contained any black members, as it had four years earlier. The New York Times, which had frequently reported the race of as many “colored” delegates as it could in 1872, was significantly less thorough this time, identifying only a handful specifically in its 1876 coverage, notably Henry Turner, former Congressman Robert Brown Elliott of South Carolina, and sitting Congressman Charles E. Nash of Louisiana, and speakers, more often simply referring simply to groups of colored delegates.

As recounted last time, the dozens of black delegates who did attend were increasingly active, winning appointment to convention committees, including Georgia’s Henry M. Turner on the resolutions committee and Louisiana’a Henry Demas on the credentials committee. The Republican National Committee list contained three black members: Pinckney Pinchback of Louisiana, James DeVeaux of Georgia, and Jeremiah Haralson of Alabama.

Pinchback, who steadfastly supported Indiana governor Oliver Morton for the presidency, was among the best-known nationally, in part for his brief role as Louisiana’s governor and for his inability to gain admission to either house of Congress, despite his election to both offices in 1872-1873. And it was his inability to capitalize on either electoral success that perhaps best epitomized his appearance in Cincinnati this year.

His recorded remarks at the convention were carefully worded to avoid any mention of those setbacks. But an Associated Press journalist, whose article was carried in the Washington Evening Star, revealed an embarrassingly lengthy summary of his vituperative remarks at what seemed to be a closed session of the Louisiana delegation, at which Pinchback angrily denounced President Grant in “disrespectful terms” and others for blocking his seating in the Senate.

In “Pinchback Attacks the President,” his “very excited speech” accused Republican leaders of purposefully blocking Senate action on his seating. “He, himself, would have been in the U.S. Senate today had it not been for Gen. Grant, Mr. [Roscoe] Conkling, and others; they feared that he wished to bring his wife into Washington society, a thing he had never contemplated.”

The complicated scenario involving Pinchback had featured his consecutive elections to Congress in November 1872 and selection by the Louisiana legislature as U.S. Senator in January 1873. He apparently chose to forego being seated for two years in the House—becoming the first black Congressman ever from Louisiana—in favor of a six-year Senate term. Against the disastrous backdrop of the political situation in Louisiana and Washington intrigues, however, he picked the wrong office, and ended up getting neither one, although the Senate finally awarded him $16,000 in compensatory damages after refusing to seat him.

Read more of the account of Pinchback’s 1876 remarks in the excerpt below:

[For a fuller explanation of the situation, see historian Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s article at https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/the-black-governor-who-was-almost-a-senator/ ].

Pinchback continued to hold appointive offices in Louisiana at both the state level and later, at the federal level until 1885. And he remained an elder statesman, perhaps because of his privately sharp tongue. But he was frequently at public odds with other black leaders across the South, including Alabama congressman Jeremiah Haralson, who genuinely supported Grant and were disappointed that he chose not to seek a third term in 1876.

Who did black delegates support instead of Grant in early balloting? It is not completely clear, but several delegations with many black delegates—like Louisiana, led by Pinchback—largely supported Indiana governor Oliver Morton (12 of 15 votes) giving just three votes to former U.S. House Speaker James G. Blaine on the second ballot.

Four other Southern delegations followed suit: South Carolina (13 for Morton, one for Kentucky favorite son Benjamin Bristow, former Secretary of the Treasury); Arkansas (11 for Morton, one for Blaine); and Texas (12 for Morton, two for Blaine, and one each for Bristow and Roscoe Conkling).

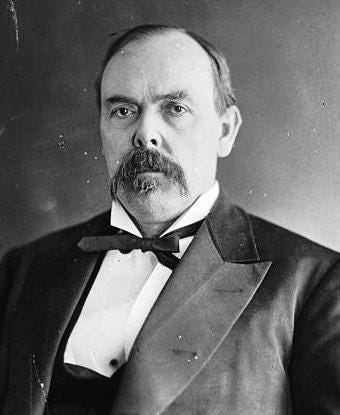

Oliver P. Morton, 1876 candidate for GOP presidential nomination. Public domain photo

James G. Blaine, 1876 candidate for GOP presidential nomination. Public domain photo

Some Southern states split almost evenly, such as Florida (four each for Morton and Blaine); Mississippi (six each for Morton and Bristow, out of 16); and Tennessee (eight each for Morton, Blaine, and Bristow). But the bare majority of Southern delegates still preferred Blaine, who received 82 of 204 Southern delegates, including those from Alabama (16 of 20); Georgia (nine of 22); Maryland (16 of 16); North Carolina (eight of 19); and Virginia (14 of 22 votes cast).

Benjamin H. Bristow, 1876 candidate for GOP presidential nomination. Public domain photo

Blaine still led among Southern delegates on the fourth ballot, by 81 to 68 votes for Morton. On the sixth ballot, Blaine had taken a marginally stronger lead nationally, gaining momentum among Southern delegates (96 to 46 for Morton). But Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes had surged into second place overall, and for the first time, had begun to attract more than a handful of Southern votes, showing 20 votes there, mostly from Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas).

Hayes would, in fact, take the nomination on the seventh ballot, with a razor-thin majority of 384 votes, out of 756 cast—or five votes more than the 379 he needed, compared to 351 cast for Blaine and 21 for Bristow. On that critical seventh ballot, Hayes drew nearly half of the Southern delegates—95 of 207 cast, even as Blaine increased his share to 108.

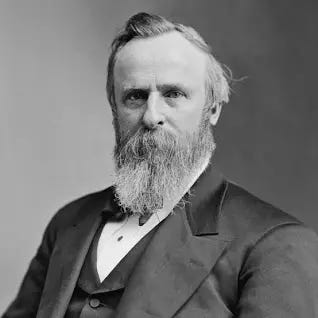

President Rutherford B. Hayes, the seventh-ballot 1876 GOP convention nominee. Public domain photo

Unanimous seventh-ballot votes in North Carolina and Mississippi, including their six black delegates, thus apparently sealed the narrow Hayes victory. Other Southern states shifted to a Hayes majority, including Tennessee (18 of 24 votes) and Texas (15 of 16 votes), bolstering his final lead in a three-candidate race. as Morton and Conkling dropped out. Morton’s dwindling sixth-ballot votes in Louisiana, Florida, and Arkansas went almost exclusively to Blaine.

Had more black delegates gravitated to or continued to hold out for Blaine, however, as they seemed to do in Georgia and South Carolina, the balloting might well have continued to an eight ballot, or even indefinitely. Without the handful of votes now cast for Hayes by the six black delegates in North Carolina (two of 20: James H. Harris and William P. Mabson) and Mississippi (four of 16: Blanche Bruce, James D. Cessor, Josiah Settle, and James J. Spelman), James G. Blaine might yet have become the party’s 1876 nominee.

The party’s prospects of defeating the Democratic nominee, Samuel G. Tilden, were uncertain at best. Hayes went on to lose the national popular vote by more than 260,000 votes, although disputed electoral votes from three Southern states—Florida (4), Louisiana (8), and South Carolina (7), the only Southern states in which Hayes may actually have won the popular vote, although none had favored him at the 1876 convention—and Oregon (3) delayed a final decision by a special Electoral Commission until March 1877. The 20 votes Hayes needed were eventually awarded to him, along with the presidency, in a controversial 185-184 electoral college victory.

Would James G. Blaine have fared any better than Hayes did in 1876? Could he have won outright, without the help of the disputed Electoral Commission? Perhaps. It is all delightful speculation, of course. He was certainly better known and more popular in most Republican quarters, although disliked by many others. And when he finally became the Republican nominee eight years later, in 1884, the situation was markedly different. Yet even then, Blaine lost to Democrat Grover Cleveland in a far closer national popular vote, by a margin of just 26,000 votes. But in 1884, Blaine carried not a single Southern state’s popular vote, losing badly in most of them and losing the electoral college by a resounding final tally of 219-182.

Now suppose, just for a moment, that Blaine in 1884 had carried those same three Southern states Hayes managed to “win” in 1876, however dubiously—and now worth 21 electoral college votes. Instead of losing in 1884, Blaine would conceivably have won the presidency by a margin of 203-198. Or perhaps, winning toss-up states Indiana (15) and Connecticut (6), which Hayes lost, but which 1880 nominee James Garfield won—and yielding the same margin.

Had the six black delegates in just two states in 1876—Mississippi and North Carolina—voted for Blaine instead of Hayes on that critical seventh ballot, James G. Blaine—the man many called the “Plumed Knight”—might well have gone on to win the nomination on the eighth ballot and face Samuel Tilden in 1876.

An outright Blaine victory that year—not at all inconceivable, based on his 1884 voting total—followed by a theoretically likely reelection in 1880, might well have changed American political history forever, all because of six long-forgotten black delegates in Cincinnati in 1876.

Next time: Seeking to renominate Grant for a third term in 1880