African Americans enter the nation's political game

Part 5: Even as Reconstruction wanes, Cincinnati beckons to black GOP delegates

The year 1876 marked an end to one political era—the two-term Republican presidency of the much-admired Ulysses S. Grant—and the inevitable transition to his successor. For many African American Republicans, this promised to be a difficult transition; their affection for General Grant, the military emancipator of Southern slaves, bordered on idolatry.

Based on my continuing research for a planned book about black participation in the Republican party conventions in the decades after the Civil War, I have been able to identify at least 54 black delegates to the Cincinnati convention, held in mid-June of 1876. Almost half of those delegates hailed from just three Southern states—Georgia (8), Louisiana (9), and South Carolina (8)—along with representatives from at least 10 other states, including New York, and the District of Columbia. In addition, at least 31 black alternates

Cincinnati delegates were the most politically experienced group yet to attend a national convention, their ranks including at least 27 current or former state legislators, along with four sitting members and three former members of Congress; two congressmen who had been elected but never seated; and one sitting U.S. Senator, Blanche Bruce of Mississippi.

As the Washington Evening Star noted in one front-page article, the mere presence of so many “colored delegates .. caused some surprise … to those who had not attended the convention held four years ago in Philadelphia,” such as “Congressmen or ex-Congressmen from South Carolina, Alabama and other Southern states.”

Indeed, more than half (eight of 14) of the South Carolina delegation, chaired by ex-Congressman Robert Brown Elliott, were black, including two of its current congressmen, Robert Smalls and Joseph Rainey. Half of the Louisiana delegation (eight of 16 members), including Congressman Charles E. Nash, and nearly half of the Georgia delegation—nine of 22 members, including former Congressman Jefferson Long—were also black.

By contrast, Alabama’s delegation was overwhelmingly white—just four of its 20 delegates were African American, including its chairman, Congressman Jeremiah Haralson.

Jeremiah Haralson (1846-1895?), Alabama delegate to 1876 GOP convention. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Just one black member of Congress, in fact, was not in Cincinnati: North Carolina’s John Adams Hyman, elected comfortably in 1874 but still trapped in Washington, awaiting his official seating by the Democratic-controlled House on August 1, 1876, after a protracted contest by his Democratic opponent.

The black delegates accounted for just over 7 percent of the entire convention’s 750-plus voters, but played an outsized role in negotiations for the selection of the next presidential nominee. Most seemed to favor the early favorite, James G. Blaine—the controversial former House Speaker from Maine, currently embroiled in a scandal over stolen letters—and Blaine’s nomination was even seconded by a black Georgia delegate, Rev. Henry McNeal Turner.

Turner and others may have been influenced by the persuasive rhetoric of non-delegate John Mercer Langston in a stirring speech delivered outside the Burnet Hotel, as reported by the Evening Star. Langston, an influential law professor and former acting president of Howard University, had similarly appeared outside the convention hall in Chicago in 1868, favoring the nomination of Ulysses Grant.

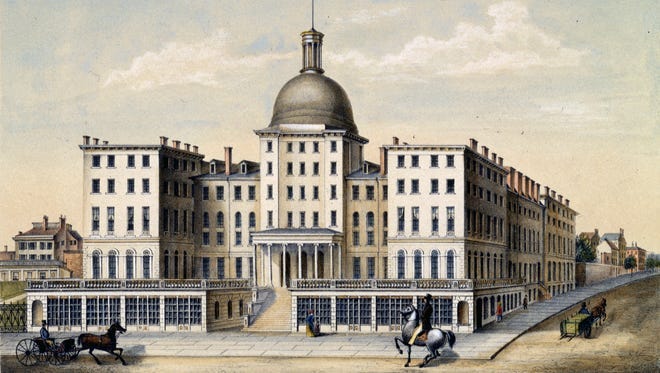

The opulent Burnet Hotel, where many delegates stayed in 1876. Lithograph courtesy Library of Congress

Other black delegates, like Louisiana’s P. B. S. Pinchback, preferred Senator Oliver P. Morton of Indiana, one of eight contenders listed on the first ballot. Nominating Morton, he declared, would protect the rights of all Southern citizens and “strike terror to the hearts of those monsters in the South who are … destroying its commerce, persecuting and murdering white and black Republicans in that section.”

Meanwhile, Southern support—whether from black or white delegates—for Rutherford B. Hayes, the eventual nominee on the seventh ballot, was lukewarm at best for the first six ballots. Most continued to cling to Blaine, who lost out only in a late surge by Hayes on the final ballot.

* * * * * *

New York’s single black delegate in Cincinnati was a controversial former abolitionist named Henry Highland Garnet [1815-1882], who had once become notorious for his angry “Call to Rebellion,” encouraging slaves to revolt against their masters, issued in 1843 at a National Negro Convention in Buffalo. [See the PBS documentary website, at https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p1537.html .]

His radical oratory in 1843 had alarmed white abolitionists and other black leaders, including his contemporary. Frederick Douglass, whose less inflammatory debate approach prevailed—if barely, by one vote.

Henry Highland Garnet, delegate at 1876 GOP convention. Photo courtesy National Museum of American Diplomacy

Garnet’s brief remarks at this Cincinnati gathering were far less strident than those in 1843, reflecting his more recent conversion to a milder-mannered man of the Presbyterian cloth. But 31 years later, his official status within this convention still outranked that of his erstwhile opponent; Douglass’s unsuccessful quest for a spot on the party’s official D.C. delegation left him as an honored but strictly speaking, unofficial speaker.

Garnet rose to beg the convention to recognize the sad plight faced by more than 60,000 Southern freedmen, whose small deposits in the Freedmen’s Savings Bank had simply vanished in the mid-1874 failure of the Reconstruction-era institution, “in consequence of the rascality and villainy of the managers.” The bank, first chartered by Congress in 1865, had badly mismanaged its loan portfolio, and its collapse left its depositors unpaid to the tune of some $3 million. His full text follows:

Garnet’s remarks may also have contained a mild, subliminal dig directed at Douglass, his longtime rival, who moments later, would take the floor to deliver his own remarks. Brought in three months before the collapse as the bank’s president as a last-ditch effort to stabilize its leadership, Douglass soon realized he had himself been duped, then swindled, after investing thousands of dollars of his own savings in a vain effort to prop up the failing institution by forestalling depositor “runs.”

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) spoke at the 1876 convention. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

If Douglass was still smarting from the lingering effects of the 1874 scandal, it showed in the somewhat acerbic tone of the lecture he proceeded to visit upon his audience. “You say you have emancipated us. You have; and I thank you for it. You say you have enfranchised us; you have, and I thank you for it. But what is your emancipation, what is your enfranchisement, what does it amount to, if the black man, having been made free by the letter of your law, is unable to exercise that freedom … The question now is, do you mean to make good to us the promises in your constitution?”

The full text of the Douglass speech follows:

Whatever their lingering personal differences, both men were cheered and applauded, and eventually gained presidential appointments as U.S. diplomats—Garnet as U.S. Minister to Liberia in 1881, followed by Douglass, who became U.S. Minister to Haiti in 1889, after stints as U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia (1877-1881) and the city’s recorder of deeds (1881-1885).

Next time: The Cincinnati convention betrays small fissures in black solidarity