African Americans join the nation's political game

Part 2: Chicago sets the standard for the future of GOP conventions

Last time, I introduced readers to my continuing research into African American political history, specifically the selection of black delegates to Republican national nominating conventions between 1868 and 1920. The convention held in Chicago on May 20-21, 1868, featured the first African American delegates or alternates from eight former Confederate states

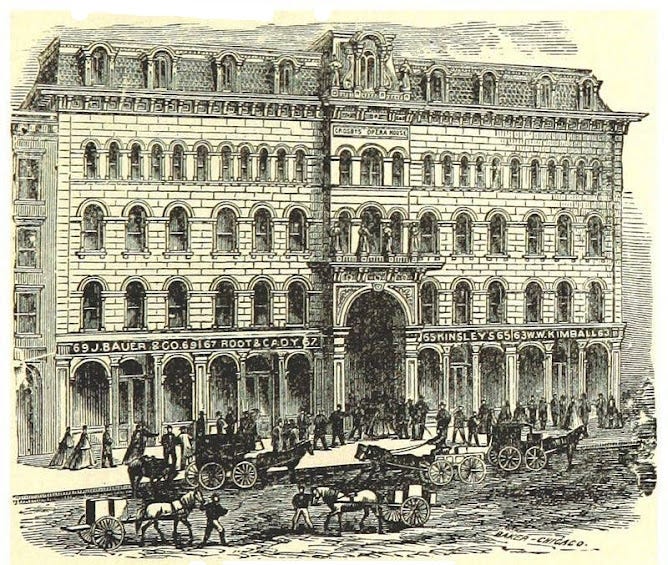

Crosby’s Opera House, located in the rear of this five-story office building on Washington Street in Chicago, hosted the 1868 nominating convention of the Republican Party. Constructed during the Civil War and dedicated just days after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, the lavish auditorium seated up to 3,000 people. The 1868 convention was the first of many to be held in Chicago in subsequent years—eight more were held there between 1880 and 1920—but sadly, the only one to be held here. After being renovated in 1871, the magnificent building was destroyed in the Great Chicago fire of October of that year, and never rebuilt.

Interior of Crosby’s Opera House, Chicago, Ill. Public domain sketch

According to Wikipedia’s article, the opera house cost more than $600,000 to build—nearly bankrupting Mr. Crosby—and was little short of spectacular. It featured a domed ceiling “encircled by paintings of Beethoven, Mozart, Auber, Weber, Verdi, and Wagner. Surrounding it were frescoes that were painted by Otto Jevne and Peter M. Almini, who were partners in a Chicago decorating firm specializing in ornamental painting.” Adorning the stage above the orchestra was “a forty-foot painting of Aurora [goddess of the dawn], based on Guido Reni’s fresco” from the seventeenth century.

The setting was certainly opulent and more comfortable than most convention halls. How much any of this helped or hindered the work of the convention is anyone’s guess. It would be another 12 years before Republicans resumed gathering in Chicago to nominate their presidential candidates—after detours to Philadelphia in 1872 and Cincinnati in 1876—but the appeal lingered for African American delegates, as well as for a small but growing group of politically-minded black leaders who were drawn to the quadrennial conclaves.

At least seven of the black delegates and alternates from 1868 would reappear in Philadelphia in 1872, when President Grant was renominated, and five of them would also attend the 1876 convention in Cincinnati, which chose dark horse Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes as the next nominee. They would be joined at those conventions by dozens of black delegates and alternates—at least 93 (51 delegates) in 1872, at least 74 in 1876—as black participants became a small but integral part of the GOP machine.

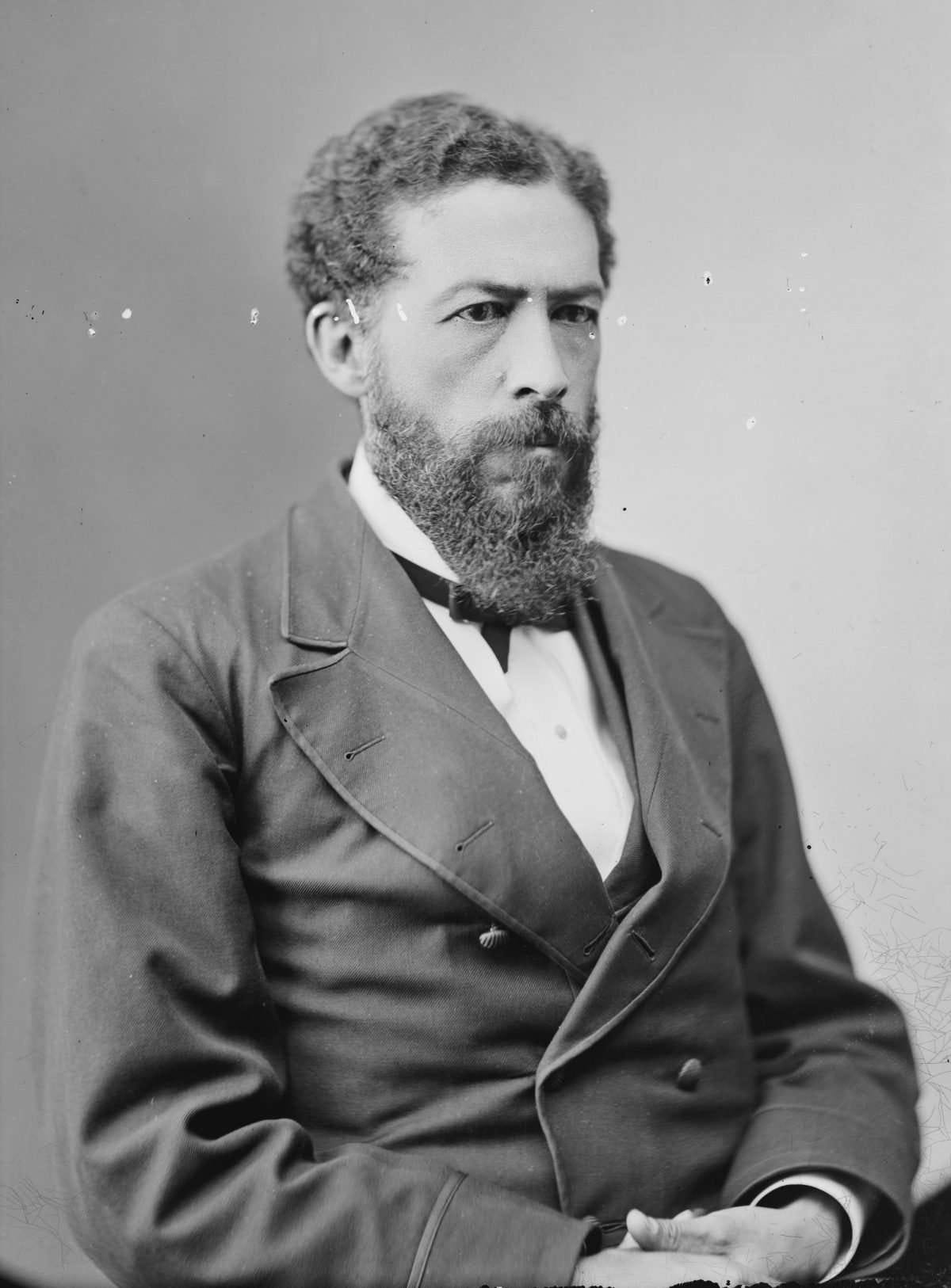

One future delegate (in 1888) who happened to be in Chicago on other business in May 1868 was John Mercer Langston of Virginia, already renowned as one of the country’s first black lawyers and arguably, the nation’s earliest known black officeholder, having been elected clerk of the township of Brownhelm, Ohio, in 1855. The prewar abolitionist leader was currently serving as general inspector for the federal Freedmen’s Bureau, and would soon become the head of the law department at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

John Mercer Langston (1829-1897), Republican congressman from Virginia, 1890-1891. Public domain photo

It is not clear exactly why else Langston might have been in Chicago on the night of May 21, when he addressed a large crowd of Republicans celebrating the nomination of Ulysses S. Grant for the presidency, but he was already a well-known figure on the national stage. Only a summary of his speech that night is available—from a longer article printed in the Chicago Tribune—but the effect of his sometimes-humorous words on the large crowd could only have been electric (italics supplied by author):

“Mr. Langston said … that the only reason that his friend [General Hasbrouck Davis] had in introducing him … was that he would lend coloring to the proceedings. The time was when they loved to court the voice and vote of the Irishman ... and … German citizens, but thanks to God and Grant, they now called on the Negro for his. In appearing before them, he was not unmindful of the fact that he represented four millions of people who never produced a traitor. … He also represented 500,000 Negro voters who knew no religion but Christ and in politics, Grant and the Republican party. Wherever the Negro voted, he gave his ballot as his voice, for the party that stood on the Bible, the Constitution, and the Chicago platform. …

“Though black, his constituency was in all things American. Again, he represented more than 200,000 black men, who in the hour of peril, in the battled between North and South, joined the Union army to vindicate justice and liberty against slavery …”

Langston might well have been rehearsing a stump speech for the Congressional campaign he would wage in Virginia’s Fourth District 20 years later, but in the years ahead, he would instead first hold a number of highly visible posts elsewhere—from Howard’s law school dean (1870) and the school’s vice president and acting president (1873-1875) to U.S. Minister to Haiti from 1877 to 1885. He would finally serve as a GOP convention delegate himself 20 years later, while campaigning for Congress.

The 1868 platform language to which he referred lies in the party platform’s first two elements (italics added by author):

“First—We congratulate the country on the assured success of the reconstruction policy of Congress, as evinced by the adoption, in the majority of the States lately in rebellion, of constitutions securing equal civil and political rights to all, and regard it as the duty of the Government to sustain those constitutions, and to prevent the people of such States from being remitted to a state of anarchy or military rule.

Second—The guaranty by Congress of equal suffrage to all loyal men at the South was demanded by every consideration of public safety, of gratitude, and of justice, and must be maintained; while the question of suffrage in all the loyal States properly belongs to the people of those States.”

On the key topic of black suffrage, the platform language was qualified. This convention did not yet endorse compulsory suffrage for all black men in all states—that would come only after passage of the controversial Fifteenth Amendment in 1870—but clearly Republicans immediately intended to enforce black suffrage in all the former Confederate states, where 90 percent of the nation’s black citizens still lived.

Like Langston, other African American leaders soon found the convention an irresistible, increasingly useful networking tool within both the party and the larger population of American blacks. Delegates would go on to serve for decades in their state legislatures, as statewide officials, and in Congress—one black Senator and at least 16 of the 20 black Congressmen elected from the South between 1868 and 1898 had already served at least once as a delegate or alternate. Many more would gain appointments to political patronage posts during the administrations of the men they helped nominate.

Over time, other state parties outside the old Confederacy would also begin choosing a handful of black alternate delegates and occasionally, even as full delegates—Missouri and Ohio in 1872; Kentucky and Maryland in 1880; Massachusetts, New Jersey, and West Virginia in 1884; Indiana and Pennsylvania in 1892, followed by Arizona Territory, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, and New York in 1896, and by Delaware in 1900.

* * * * * *

Most of the black delegates and alternates who were chosen in 1868 lived long and productive lives after their first experience at a national nominating convention. Most would return at least once. A handful died far too young, most notably James Lynch of Mississippi, who was subsequently elected as Mississippi’s Secretary of State in 1869 and then returned as a delegate in Philadelphia in 1872, where he became one of the first three black men to address a Republican convention. (Arkansan William Grey and South Carolina congressman Robert Brown Elliott also spoke.)

Lynch’s lengthy speech there was so impressive, according to the Mississippi Encyclopedia, that he was asked to serve as a campaign speaker for President Grant’s reelection, but was suddenly unable to do so for reasons of health. Diagnosed with Bright’s disease just weeks after the convention, he succumbed in December 1872, aged just 34.

Over the next three decades, others named in 1868 would become regular features at GOP gatherings, including James Harris of North Carolina, a longtime state legislator and unsuccessful candidate for Congress, who attended the next five conventions; South Carolina’s Charles Wilder, who attended the next four conventions and a fifth one in 1896; and future congressman Robert Smalls of South Carolina, who was chosen to attend seven of the next nine conventions, the last in 1904. (After leaving Congress in 1887, the highly influential Smalls was appointed federal collector of customs at the port of Beaufort, holding that post for 19 of the next 23 years.)

Louisiana’s P. B. S. Pinchback, who served as lieutenant governor and briefly as acting governor in the 1870s, remained politically active for decades, winning disputed elections to the U.S. House and Senate, but not seated in either body. Pinchback attended five of the next six conventions, his last appearance coming in Minneapolis in 1892. South Carolina’s Swails was named to attend three more conventions (until 1888), while South Carolina’s Elliott attended three more in a row, until 1880. South Carolina’s Joseph Rainey, Wilson Cook, and W. Beverly Nash, and North Carolina’s John Leary were each chosen to attend two subsequent conventions, as was Mississippi’s Rev. Thomas Stringer.

Arkansas’s William Grey (1872), Texas’s George Ruby (1872), North Carolina’s John R. Page (1876), and South Carolina’s Henry Shrewsbury (1880) and W. J. McKinlay (1876) each attended just one more convention.

Other delegates and alternates disappeared into relative obscurity nationally, like Virginia’s George Teamoh, an Alexandria state legislator who disappeared from the public record around 1887, and all of Tennessee’s representatives in 1868; none appeared in lists for later conventions. Little is known of the later lives of delegate A. N. C. Williams or alternates M. G. Carter and Abram Smith, but we do know that one alternate—A. T. Woods, 53, selected from Tennessee’s Fourth District—died of apoplexy a week or so before the delegation would have left for Chicago.

Woods was the 29th name on my original list, reportedly a physician who lived for a time in Murfreesboro and advertised for patients in at least one Nashville newspaper the year before his death. Unlike all his convention companions that year, however, Woods appears to have been a complete fraud—twice jailed for fraud, in both the United States and Great Britain, with no academic credentials. In short, an impostor now masquerading as a man of medicine in postwar Tennessee.

His real name, according to historians and a lengthy newspaper article, was George Andrew Smith, born in Canada, and apparently never naturalized as a U.S. citizen. For 20 years and more, Smith had posed “as a man for all ‘seasons’ on three continents”—Africa, Europe, and North America—by claiming variously to be “Oxford educated, Cambridge graduate, theologian, missionary, architect, author/ historian, teacher, Senate chaplain, (and) skilled physician” before his final act as a political player. His death ended his life, if not his mystique; the sheer extent of his fraud was not revealed for decades.

For more details, you can check out the fascinating complete story at this website:

https://rutherfordtnhistory.org/remembering-rutherford-curious-smithwood-odyssey-concluded-in-rutherford-county/ .

Next time, I will examine the growing participation by Southern blacks at Republican national conventions, beginning with 1872.

Next time: African Americans help renominate Grant in Philadelphia in 1872

HI Rede--I guess I zoned out on the so-called Black National Anthem, a song which I find eminently forgettable, but to tolerate--having heard it so many times at different events. I know a little about its history but never found it as appealing as either of the anthems I was raised on--just difficult to sing (like the Star-Spangled Banner)--to each his own, I guess. Langston Hughes, the poet , was great-nephew to John M. Langston (mother's uncle, who did before Hughes was born). So far, the death rate of black delegates/alternates has proved very low--no violence--just bad health in general, for many of those who did pass away soon after. Untreatable diseases back then--high blood pressure, diabetes, Bright's disease--often claimed middle-aged black men.

Hey, Ben! Been wondering about you since the black national anthem / superbowl brou-ha. James Golden did a great onair dissertation on the origin of the text (a poem) and music (by the poet's brother) and I wanted to get your take on the whole [I need some creative expletives here for the political stupidity in evidence] ao this is my fist chance. // A couple of questions for you. You mention someone name of Langston -- anything to do with Langston Hughes? Next: has there ever been any question about the number of delegates/potential delegates/etc. dying before they got to their office(s)? Yes, I know, we need not visit conspiracy theories on past generations . . .