A nostalgic farewell to my childhood home

Part 2: A long walk off a short pier into not-so-shallow water

Last time out, I began telling readers about the complicated decision to sell my childhood home, which my sister and I inherited after our Mother’s death in 2019. For years, it was a writer’s dream for me—a quiet haven in a dull world, far from the busy noise of suburban Washington, D.C., where I lived until 2021, and then from my bustling pre-retirement condo in Broward County, Florida.

Pal Benji calmly contemplates giving up the past at his granny’s home at 210. Author’s photo

Despite our best efforts, Beth and I could not manage to hold back the ravages of time on the aging house—and encountered gradually worsening problems with both its “innards” and its exterior, which required substantial investments to resolve. We were already sinking about $600 a month into my “vacation” home, which she rarely visited unless I came up from Florida—and the thrill of homeownership had begun to fade by December 2023, when I drove up in early winter to find our ancient furnace threatening to give up the ghost. Because it supplied hot water to both the kitchen and bathrooms and the radiator heating system, this was worrisome in suddenly sub-freezing weather.

The house still had plenty of hot water, thanks to the natural gas-fired boiler. (More on that later.) The creaky old radiators in every room, however, were less than cooperative, so I began using those portable oil-filled electric radiators I had purchased for my Mother as a supplemental source of heat during her final years as queen of 210. The technician I finally managed to locate shook his head and reminded me that this 72-year-old furnace had just about outlived its original lifespan; it had run on home heating oil from a buried tank for the first 40 years or so, until Mother had agreed to convert over to newly-available natural gas. It would never again run as well as it should, he warned, and we ought to think about installing a new HVAC system, period.

Mother had long used window air-conditioning units—three of which I had replaced for 210 either before or after her death—and that meant finally installing a central a/c and heating system with overhead vents—after cleaning out the overfilled attic to allow workers to get up in it. I shook my head at the estimated cost, which also included an upgraded electrical circuit-breaker system capable of supporting a new HVAC system.

I already knew the roof would need to be replaced within a few years; the wooden siding was in dire need of painting and partial replacement, and new windows were not far beyond that in our future. Was spending that much money on a house neither one of us really used that much really worth it? I wondered. So next, on the weekend before Christmas, I called in a representative from a well-regarded firm that advertised itself as a solution to homeowners in my cash-strapped predicament.

The helpful representative came and walked me through the process. I won’t go into specifics, except to say that he did warn me that investor offers had both advantages and disadvantages. They were all cash, which meant no waiting for mortgage approval—a relatively quick turnaround, in most cases—but there was no guarantee that the prospective circle of investors would produce the desired number of competing bids, the optimal scenario, from which you could choose.

In a mid-winter market, with a very slow-moving housing inventory, it was all a bit of a crapshoot—but there was no real obligation if it did not produce an offer to our liking. We were NOT required to repair anything, although we were going to clean 210 out and spruce it up as much as we could, anyway—just for pride of ownership—and hope for the best.

And just in case the investor route did not work out, this particular firm also offered a traditional public-showing strategy as a fallback. Again, we were not obligated to sign up for that second step, but at least had the option. For informational purposes only, I had actually talked to a local real-estate firm a year earlier about prospects—during the much hotter market, when houses in my sleepy hometown were still selling like relative hotcakes—and had even discussed it with a neighbor who dabbled with investing in and flipping houses. Neither discussion had produced any helpful results.

I will say this much. We decided, on more of a whim than a well-considered and carefully-evaluated thought process, to give investors a chance to bid on my property. We were not naive; we did not expect top dollar, but simply set a price near ideal market value, for starters. I knew that the typical investor bid would probably come in at about 75 percent of market value, and the serious bids would then be negotiated for final acceptable price, timing of settlement, and other details.

What I did not know, and learned to my unfolding chagrin, was just how devious the investors would turn out to be. At least four investor offers—all lowball experts, including one crazy-quilt “hybrid” offer (let us temporarily take control of your property, repair it, and sell it ourselves), which we immediately rejected—came and went, sequentially. Along the way, I became convinced that the small circle of people with ready cash all knew each other and were simply passing our property down the line, refusing to bid against each other—well, seems they did not like my low offer, maybe you can offer them a little bit more and see. And so much for “as is” or “no repairs needed,” as we discovered.

All but the final one collapsed in mid-stream, as each buyer decided upon due-diligence inspection that no, he or she could not actually stick to the initial offer, and we either had to accept less or walk away. We actually kept a due-diligence deposit after one investor decided at the last minute that 210 was suddenly too expensive to repair, and lowered her initial lowball bid by more than 25 percent—but only after browbeating us into digging up the underground oil tank, emptying it (!), and having it hauled away (at a cost of more than $4,000).

That was disheartening, underhanded, and to my mind, at least, bordered on unethical—if perfectly legal, and apparently prevailing investor practice. The annoying part, of course, was that we had taken it off the market for weeks to allow it—and thus missed any chance to show it to more sincere buyers, which I am certain she figured into her calculated strategy. But today’s real-estate world apparently belongs primarily to sneaky or outright crooked investors, especially during slow economic times.

I have to note here that my hometown is a peculiar world unto itself, both in many of its provincial social ways and in its relationship to the outside world. Nothing that works anywhere seems to work very well, when it works at all, in the “best town under the sun,” as it once proudly proclaimed itself—the tired town that time forgot, I call it—one reason why it is not growing, still stuck at the almost-9,000 population of my youth 50-odd years ago, despite its advantageous geographical location between major urban centers of Fayetteville and Raleigh and its proximity to two major Interstate highways.

Tearing down the 19th-century railroad depot when Amtrak decided to quit stopping there in the 1970s was the first in a long line of dumb, shortsighted decisions that town fathers foolishly allowed and encouraged—instead of fighting Amtrak, as nearby Selma successfully did. Losing it disemboweled downtown—and with it, so much town history as a railroad village began to wither and blew away. Amtrak’s Miami-bound special still roars through periodically, clogging traffic on both sides of the crossings, especially at noon, but travelers have to drive 25 miles to Fayetteville or Selma to board it.

The Dunn railroad depot, ca. 1890, torn down in the 1970s. Photo courtesy Dunn Area History Museum

Their inaction doomed the town, in my estimation, to dusty oblivion, not prosperous growth, despite occasional, half-spirited efforts to dress up a dying downtown retail center gutted by Walmart and suburban sprawl toward the county seat, Lillington, and every other small town within a 30-to-35-mile radius, where new subdivisions are springing up almost weekly.

Harnett County, long moribund when I was born, has nearly tripled its population since 1960. But not Dunn … pleasantly dull, it has its good points, yes, and many good people, but what it lacks are vision and commitment, and imaginative leadership; there is so little to do that tornado threats and hurricane warnings are almost welcomed as a diversion.

It may still appeal to some homebuyers, primarily those rare newcomers, as a cheaper alternative and an easy commute to Fayetteville (25 miles) or Raleigh (40 miles), and the property tax rate is comparatively low—although both Interstates are increasingly choked with traffic. The prices that have appeared in some of the few newer local subdivisions are frankly, astonishing to me—if far below Raleigh’s fantasy-world prices. We knew we could never compete with far newer or larger and better-maintained homes in town.

Above all, we had refused to consider renting it—the kiss of death to so many older homes in town, including three just across the street—but had secretly hoped someone would appear and adopt our beloved 210 as a labor of love, repairing and gradually updating it for use as a warm and appealing home in the 21st century.

Realistically, however, Beth and I knew how unlikely that was to happen. When we finally bit the bullet in April and prepared to start showing the house to the public in May—with wonderfully staged photographs—after selling off much of the furniture and belongings, giving away what was still usable to secondhand stores, and throwing junk away, we still hoped it might, and we did have a few visitors express interest. The house is old, yes, but still handsome, with a distinctive design and a stone facade on the front—reminiscent of the stone houses my cowboy and war hero Daddy grew up with in Utah—and it has such promise and such good “bones” for a buyer with any kind of fix-it mentality.

But the truth was, no one really wanted our stable neighborhood or tall, beautiful trees, or gorgeous backyard, enough to come back a second time. In truth, the neighborhood had changed a bit since we moved there—in the 1970s, the town completed a dedicated but never-connected street, which now runs busily between 210 and the neighboring house; and the ditchbank and woods my neighbor Tommy Harrall and I used to roam were long gone, given up to developers. All those wonderful backyard parties and barbecues and summer evenings chasing lightning bugs vanished … all those Christmas and Thanksgiving dinners with my Mother’s large extended family reduced to photographs and wistful memories…

The rear driveway and backyard at 210—a kid’s dream, minus swings and a basketball goal. Courtesy Zillow.com

Despite its “good bones” and the wonderful professional photographs shown online, 210 was sadly not right for everyone in person. With just two bedrooms, it was basically too small for a family with more than one child. We kept attracting pesky investors, like mosquitos, with almost-insulting lowball offers that shrank or withered away on closer examination. Apparently they were all we could expect …

* * * * * * * *

Meanwhile, the grueling process of cleaning out 70 years of accumulated stuff was wearing us down. It was like taking a short walk off a long pier into water you thought was shallow … and feeling instead like you had stepped off the continental shelf.

We finally sold Mother’s fine china and crystal to thrift stores. We cleaned out the attic, which was almost a horror show at times—including my Daddy’s rifles and shotguns, left over from when he used to hunt in the 1950s, and thousands of badly-deteriorated negatives from his days as a commercial photographer—when he actually had a working darkroom, later converted into a second bath. A friend who owned one thrift store agreed to buy almost all the furniture for a fair price—Mother’s wonderful old pieces, built up over 40+ years of marriage—including some antique items that in a perfect world, might have sold individually to dealers elsewhere, and larger mid-20th century items which neither of us had room for, and no one else in the family wanted, either—and hauled it all away, in three separate trips.

Hundreds of our treasured hardback books went to the Wake County library system in Raleigh, which accepted almost anything but, disappointingly, then sold the books through an online site without sorting them or keeping any. I made endless trips to Habitat for Humanity’s local ReStore shop, with anything they would take and resell, and took old clothes, sheets, and blankets to the Beacon rescue mission shop. Trips to the county solid waste landfill—affectionately called the “dump”—thinned out the rest of the mess in the meantime.

I shredded papers, filled the recycling bin with magazines and worn-out paperbacks, gave old newspapers to the local museums; I donated a set of outdated but still usable Britannica encyclopedias and dozens of useful historical reference books to a nonprofit community center in Bladen County I support, and at which I spoke during my two-month “working vacation.” Many of those books were related to George Henry White and his 19th-century era, the subject of much of my academic research over the past 25 years. I hope they bring a new generation as much pleasure as they gave me.

The George Henry White Memorial Health and Education Center near Clarkton, NC. Courtesy www.georgehenrywhite.com

I worked day and night for two months, desperately trying to finish the job I had started so that more showings might be scheduled, at least, with minimal staging items left behind. Rather than throw away some of the things I could not yet bear to part with—a very few pieces of furniture, a few paintings and prints, some of the books I simply did not want to be sold at a library auction—some of which I still hoped to take to my Florida condo, but could not fit in my sedan—I did the one thing I had promised never to do again: rent a small storage unit, which was full by the day I left Dunn in early June. (I still need to go back in August and face that task. I dread it, but at least it’s now just a roomful, down from a houseful.)

It was emotionally and physically exhausting work, easily the hardest single task I have ever had to perform. I did not hurt my fragile back—mirabile dictu, as my Latin teacher used to say—but my psyche suffered; I cried more than I care to admit when sorting through old photos and private papers, as my childhood flashed in front of me. Even cleaning out our family’s beach house for its 2004 sale to a developer who immediately tore it down (because the lot was worth more than our 50-year-old, two-story house) could not compare, nor the nightmare of cleaning out its flood-damaged ground-floor apartment in 1996, after Hurricane Fran submerged much of Wrightsville Beach under five feet of sewage-contaminated seawater.

Hurricane Fran makes N.C. landfall in 1996, flooding my family’s vacation home in Wrightsville Beach. Courtesy Wikipedia

During both sad events, it was Beth and I and Wayne Jr., still with us back then, who did most of the grunt work for Mother. We were all so much younger then …

Now nearly 75, I lacked the strength or stamina for this task, but I persisted, somehow. And by the time I left, cleaning out 210 was miraculously down to a few days of finishing work that Beth and her husband Bryan figured they could handle alone. What we learned, to my horror, was that we were now to be visited with a Biblical plague of sorts: a sudden infestation by fleas, which poor Benji had unknowingly brought in from the yard, I guess. He has never had a flea problem before, but because we had stopped giving him preventative medication in Florida due to some unrelated health issues, he developed one, unawares—I learned this only when I got him home and we had him shaved and bathed.

Without a “host,” the half-carpeted house he and I had lived in for the past two months turned overnight into a haven for swarms of the dastardly little creatures, which attacked Beth the next time she entered. We were still entertaining the next-to-last offer, before it imploded without warning, just two weeks before its scheduled closing. I had already planned to have an exterminator spray for roaches, which had infested the dozens of cardboard boxes we used to cart away books and items for the dump, when the house was finally empty.

But now that had to expand, and immediately. And that meant suddenly closing the house off to any and all showings and any potential buyers while I scrambled to find a local exterminator—who at least came quickly. That same week, the next-to-last offer fell apart.

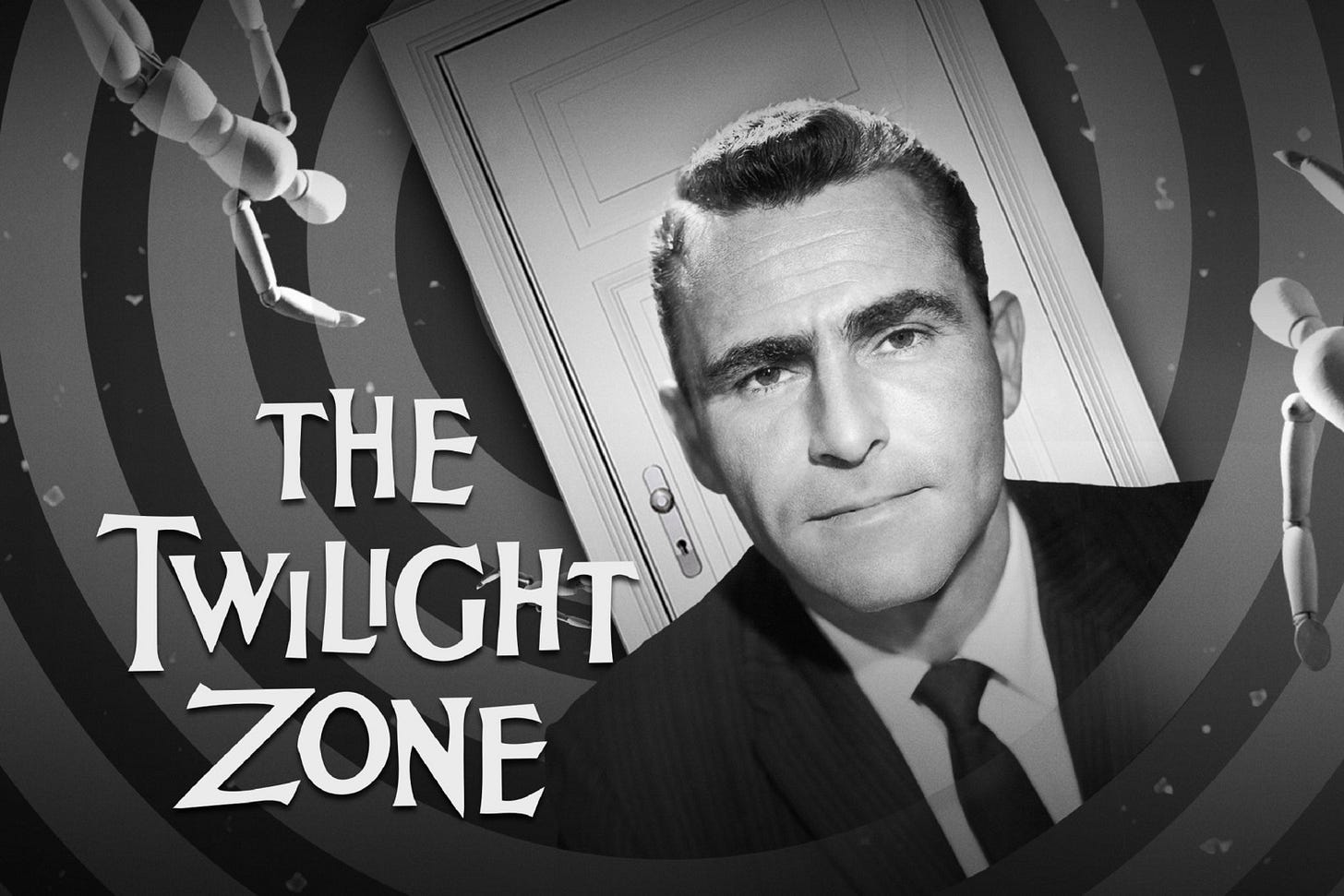

That the online appointment center was, simultaneously, suddenly breaking down my virtual door—calling and texting me at all hours—with new or repeat requests from real estate agents, made me wonder whether I might have wandered into the “Twilight Zone,” and would meet Rod Serling any minute. Just my luck. With our last offer now in shreds, I had to refuse more than a dozen new requests to peek inside, without explaining why … we could not risk a disaster …

I was stuck back in another era. I could easily have been Gig Young in “Walking Distance,” the episode from the opening season in 1959, where he finds himself trapped, temporarily, in the long-vanished world of his idyllic childhood and encounters his younger self … but without the carousel or ice-cream soda fountain. I had no desire to live in the ‘50s again, and no, I did not meet my 10-year-old self—’tho one of my father’s large framed photographs of me did turn up in the attic (creepy!)—but for all practical purposes, I stepped back and forth over the invisible barrier into a world long gone for two months.

My childhood came back to haunt me, lovingly, in a live version of Rod Serling’s TV classic. Photo courtesy www.rollingstone.com

The exterminator did come—bless his heart!—although it took three separate sprayings to kill off all the fleas and their newly-hatched eggs—and two weeks later, the house was finally deemed ready to show again. It was during that two-week period that our final offer materialized—from an investor on the sidelines for weeks, slowly working his way up the price ladder—and we decided it was a sign from above. If the price was still less than we had wanted, and far below the artificial price we had originally set as a starting point for bargaining, we were worn out from our stop-and-start experience of the past six months. We just wanted out.

So Beth and I took what was almost certainly his final offer—and had the last of the furniture carted away. This time, no repairs, period—truly “as is”—and no counter-offers. Just cash. We crossed our fingers. This time, against the odds, it worked; it closed last week.

* * * * * * *

It is already fading in my mind’s eye, now. The developers have taken down almost all the trees—why do they do that, I wonder, mystified? Yet I will always look back on 210 as an integral core of my past memories. I may no longer own it—but I will always hope against hope that someone with young kids will finally get it, after it is “flipped,” a family who will find the warmth and stability of my childhood there, and love it as much as I did. But I have finally moved on—homeless, but relieved.

The agent we’d dealt with made a difficult process as easy as he could, and I thank him for that. What went wrong with our sale was not his fault. The problem is the kind of buyers the investor strategy attracts. It finally worked, but I would not recommend the route we took to anyone else. It markets itself as simple and user-friendly. Simply put, it is neither. It is complicated and frankly, nerve-wracking.

But it is done. So what’s next? I will still come back, occasionally, to North Carolina to visit Beth in Raleigh, my grandkids in Wilmington, and the graves of my parents, my nephew, my brother, and my grandparents in Dunn, and drop in on the wonderful new neighbors I had come to know—and their dogs, all Benji’s new friends—during my frequent visits. I will still come back to attend Sunday services at my childhood church, which remains a peaceful beacon of hope.

I was born a Tar Heel and will happily die one … it’s in my blood … and Dunn will always be my home. But this time, he (with a flea collar) and I will pay to stay in the nice bed and breakfast just up the road: a hundred-year-old mansion, nicely renovated and waiting for me. Where I can relax and not worry about a thing going wrong ,,,

Next time: Returning to 19th-century political research