A look back at the 1900 presidential election

McKinley vs. Bryan in a rematch of 1896, with a twist...

In my ongoing research on African American political participation in the late nineteenth century, I became fascinated by the runup to the 1900 presidential election — the last in which many black Southern voters were able to particpate for decades, and the role played by William McKinley’s black surrogates. Before I conclude my excerpts from my planned book on the subject, with a study of the 1904 Republican convention, I will take a slight detour into the 1900 campaign, examining the impact of racial issues on the final outcome.

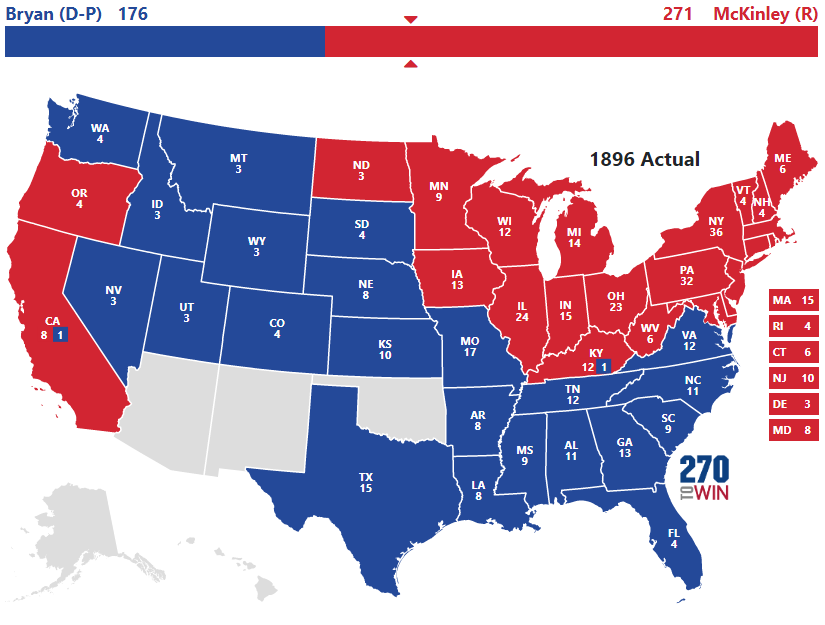

First, a little background. William McKinley had easily won renomination at the 1900 GOP cnvention in Philadelphia with majority black support, after a promising first term in the White House. His 1896 victory had been convincing, if not overwhelming: defeating Democratic-Populist nominee William Jennings Bryan by 271 electoral votes to 176, as well as a significant popular victory (7.1 million votes to 6.5 million).

Bryan had swept the Solid South and most of the Midwest and West, losing beyond the Mississippi only in five states: California, Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Oregon, with a total of 38 electoral votes. Even had he won those states, he would still have lost the race nationally, 234 to 213 (California had given Bryan one of its nine electoral college votes).

Results of the 1896 U.S. presidential election. Map courtesy https://www.270towin.com.

Disaapointing as the overall outcome in the South had been for Republicans, the race was much closer in a handful of states where Republicans still received more than 45 percent of popular votes cast: North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. North Carolina voters, in fact, had given the state its first Republican governor in a quarter of a century, thanks to state-level fusion with the Populist third party and thousands of ticket-splitters who favored Bryan for president.

And this is almost certainly where the 1900 reelection strategy was born. As president, William McKinley spent much of his time pursuing two domestic causes that in retrospect, at least, seem irreconcilable: promoting black political participation in the South by appointing hundreds of blacks to federal patronage positions, including postmasterships, despite the alarming increase in lynchings and the spread of disfranchisement, while simultaneously cultivating Southern Democrats—in hopes of carrying one or more of those Southern states in 1900.

His December 1898 visit to Atlanta for the Peace Jubilee—marking the end to the brief war with Spain—attempted to mix those two dissonant goals, combining speeches at two major black colleges in Savannah and Tuskegee with speeches to all-white audiences in both states’ legislatures. He was determined, he often said, to be president of all the people—both races and both parties—without a partisan litmus test.

That meant that he refused to stop appointing black postmasters—more than 100, mostly in North Carolina and South Carolina, by 1899—even in the face of a violent backlash, including the 1898 murder of a black U.S. postmaster in all-white Lake City, South Carolina. He welcomed thousands of black volunteers in the war against Spain, despite resistance from some quarters. Late in 1898, he boldly insisted on commissioning more than siz dozen black military officers—the largest number in history, against the advice of his own War Department—in the runup to the Philippine occupation, where many black soldiers were headed after the war with Spain ended.

If he did not act to desegregate the U.S. Army, he nevertheless insisted that segregated black regiments deserved their own black officers—no matter how much this angered Southern congressmen. But by 1900, his commitment to appointing blacks as postmasters, at least, had begun to subside, quietly but surely—in part because no action was warranted. (The four-year terms of those he had appointed beginning in 1897 would not expire until 1901 or later.)

And while McKinley continued to meet with black supporters and listen closely to what his black advisers were telling him, he remained wary of activist calls for an antilynching bill in Congress and a reduction of census-based Congressional representation in Southern states which had acted to disfranchise almost all of their black voters.

Arguably, his political strategy was flawed and shortsighted, perhaps even hypocritical—although he was clearly the best benefactor the race had ever had in the White House. His highest-ranking black appointees, Treasury Register Judson W. Lyons and D.C. Recorder of Deeds Henry P. Cheatham, spent much time on the campaign trail, hammering home this message to wavering black voters, along with the nation’s only black Congressman—George H. White of North Carolina—and Ohio’s John P. Green, a former Ohio legislator now serving as Postage Stamp Agent, highest-ranking black appointee in the U.S. Post Office Department.

Judson W. Lyons, one of the President’s most energetic campaigners in 1900. Public domain photo

John C. Dancy, another McKinley advocate in 1900. Public domain photo

Ex-Congressman Henry P. Cheatham, a McKinley surrogate in 1900. Public domain photo

John P. Green of Ohio, a tireless speaker on the McKinley trail. Courtesy www.ohiostatehouse.org

McKinley also drew the individual endorsement of influential leaders of two nationally-known black organizations, the National Afro-American Press Association (founded 1890), and the National Afro-American Council, the country’s first truly nationwide civil rights organization, established in 1898. Both were nominally nonpartisan, and declined to give group endorsements to McKinley; while most of their members were Republicans, had agreed not to cross that line in public, at least, in deference to their smaller but growing Democratic contingents.

Some of those blacks endorsing McKinley in 1900, however, were far less enthusiastic about his choice of a new running mate to succeed the late vice president, Garret A. Hobart. Theodore Roosevelt, the young govermor of New York, was a popular war hero and energetic campaigner—but had made disparaging and inaccurate remarks about black soldiers fighting alongside him in Cuba in a series of Scribner’s magazine articles published in 1899, alienating many of those soldiers and their families. The stark comparison with President McKinley—who had warmly praised black soldiers he fought alongside in the Civil War—was disheartening, although many black leaders did their best to play it down.

There was little option for black Republicans, of course. McKinley’s Democratic opponent, William Jennings Bryan, wildly popular in the South, was far less sympathetic to racial issues than McKinley—and considered by some to be openly racist. His running mate in 1900 was former vice president Adlai E. Stevenson (1893-1897), who had once served as assistant postmaster under Democratic president Grover Cleveland—and in 1885, acted to fire thousands of Republican postmasters appointed during the Garfield and Arthur administrations—including a handful of black postmasters—and replacing them all with Democrats.

Black surrogates, including Lyons, Green, and George H. White successfully preached the party gospel to black voters in Ohio and key GOP states—and arguably bolstered the party’s narrow majorities over 1896. An invaluable aid in recruting black voters in the North and Midwest were Judson Lyons’ carefully-prepared pamphlets, Appointments Which Afro-Americans Have Received Under President McKinley and A Republican Text-Book for Colored Voters. [Text of the latter is available for viewing at the Library of Congress website, at https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t1615/?sp=1&r=-1.167,-0.052,3.335,1.612,0 .]

But with black voters now all but powerless in the South, there was virtually no campaigning by Republicans in the region at all. In North Carolina, George H. White, the last black Congressman for nearly 30 years, chose not to seek a third term, and Democrats swept the entire state, including his heavily-Republican congressional district.

George H. White, North Carolina’s black congressman, declined to run again in 1900. Public domain photo

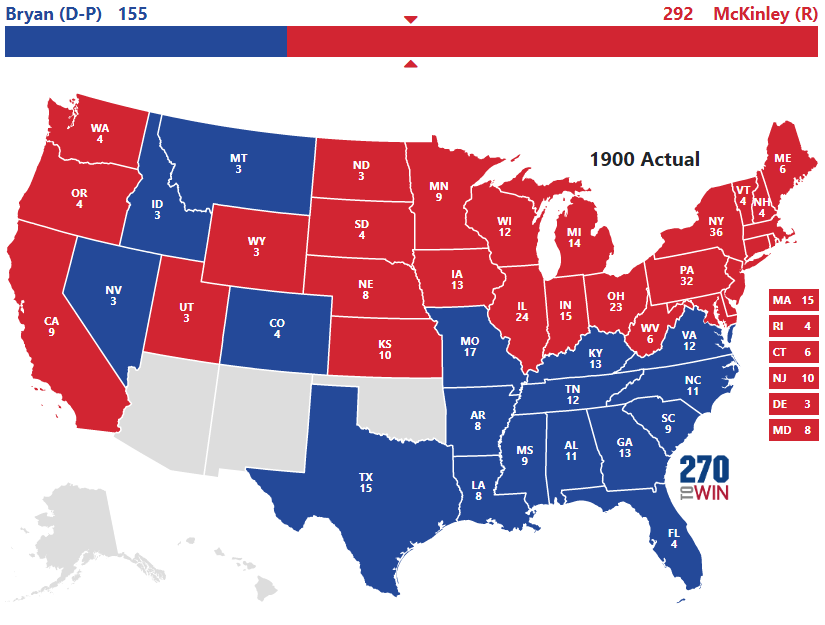

In the November election, McKinley actually improved on his national tally from 1896, winning 7.2 million votes and 292 electoral votes, while Bryan’s total declined slightly to 6.4 million votes and 155 electoral votes. But McKinley again failed to win a single Southern state—with his totals declining slightly in the three states he had hoped he might win; his closest loss came in Kentucky, where the margin was less than 2 percent. Yet he did win six Midwestern and Western states he had lost in 1896.

Results of the 1900 U.S. presidential election. Map courtesy https://www.270towin.com.

William McKinley would be sworn in for a second time in March 1901, this time with Theodore Roosevelt at his side. But African American hopes for a resurgence of the appointments of 1897 and 1898 were short-lived. Six months later, an assassin’s bullet would make Roosevelt the youngest U.S. president in history.

Next time, I will examine African American participation in the 1904 Republican convention in Chicago.

Next time: Nominating Roosevelt for a full term in 1904